The terrible events of World War I not only changed the world in terms of geopolitics, warfare and technology, but also had a powerful effect on developments in the world of art. Many of Europe’s most inventive artists, shaken by the war, gave up the iconoclastic styles they had experimented with at the beginning of the 20th century and retreated to the safer position of working in traditional styles in a movement known as the “Return to Order.” Picasso and Braque ditched Cubism, and the Italian Futurists left behind their frenetic prewar glorification of speed and modernity.

When I saw the postwar work of André Derain (1880-1954) in the exhibition “Derain, Balthus, Giacometti: An Artistic Friendship” (continues through October 29 at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), I found it uninspiring and longed to see some of his wildly colorful Fauve paintings from before the war. Now my wish has come true with “Derain: The Radical Decade” at the Centre Pompidou (through January 29).

The picture presented by the exhibition is more complicated than I expected, however. The “radical decade” explored by the show is 1904-14. It begins with a strangely modern copy of a Renaissance painting of Christ’s calvary by Biaggio d’Antonio, made by Derain in 1901, which does not fit the show’s timeframe and is off-topic. That is followed by a few lovely, folksy drawings of people working in the fields, then a series of photographs taken by the artist, many of them quite accomplished and some of which he turned into paintings.

One large painting is scrupulously based on an anonymous photo taken at a suburban dance, an amusing scene in which a man dances formally with a woman much taller than him, his outsized white-gloved hand splayed over her hip.

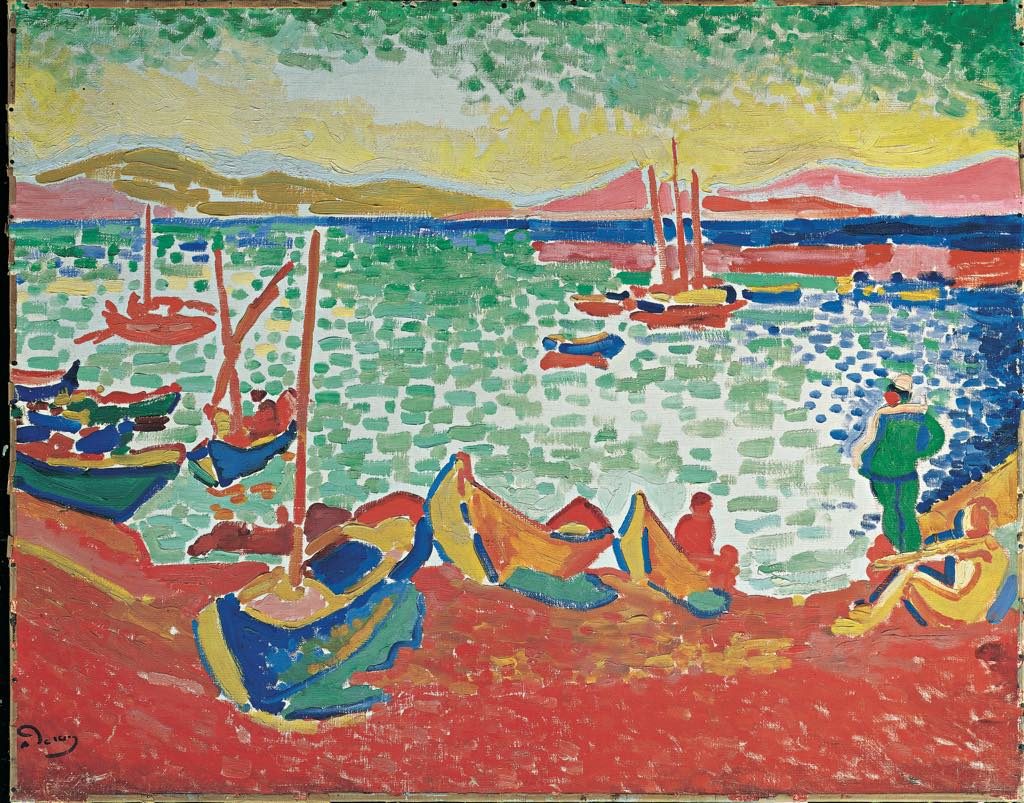

After some more drawings, we finally get into the meat of the exhibition, Derain’s Fauvist paintings. The walls explode with riotous color, perhaps not with the same wild intensity as in his friend and fellow Fauvist Maurice Vlaminck’s works, but in a highly pleasing way.

The palette lightens up when he discovers the Côte d’Azur, as in the luminous “Les Montagnes à Collioure’ (1905). Most of the paintings from this period are built of big daubs of paint in the Cézannian way of building up shapes without outlines.

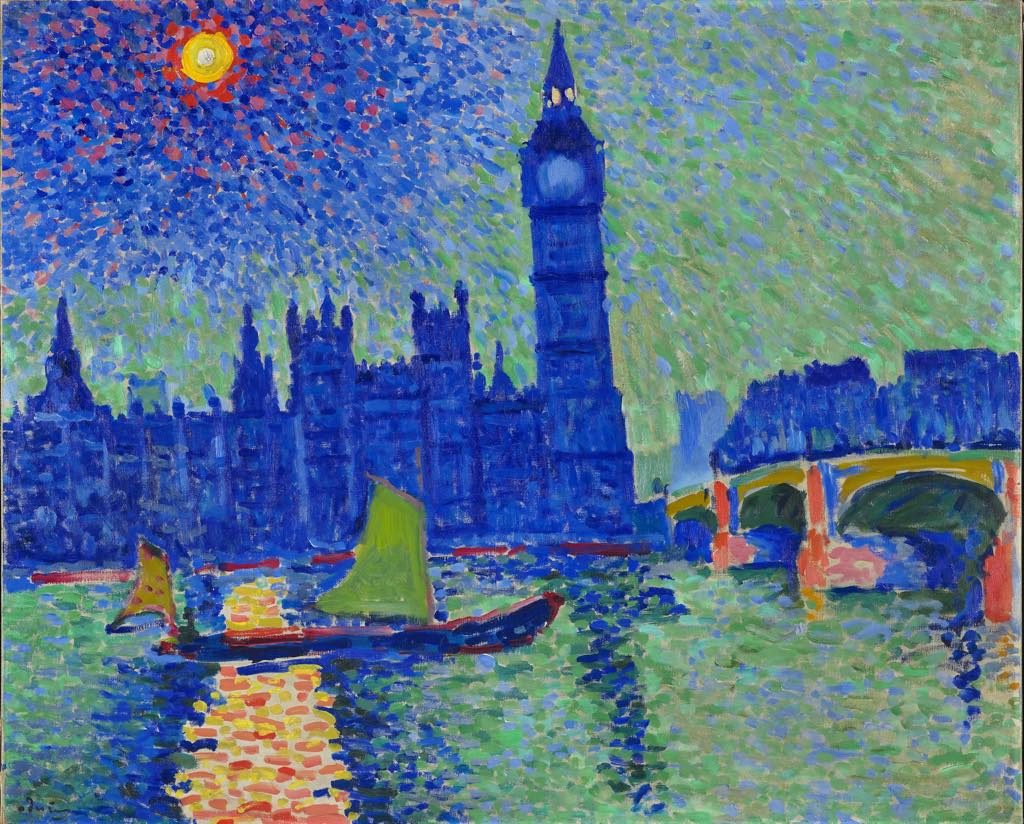

After having fallen under the spell of these dazzling candy-colored paintings, including scenes in London that make Monet’s shimmering views of the city look a bit pale, it comes as something of a surprise to come across a room full of portraits that look as if they were painted in the midst of a severe depression. The colors have dimmed and the expressions on the faces are grim, as in “Samedi” (1913), above. Most of these were made in the run-up to World War I, which might legitimately explain the artist’s bad humor.

He managed to survive the five years of the war, in which he served as a gunner, but he was not unscathed, and the results can be seen in his rejection of his prewar style. From then on his work mostly seems proficient but dull.

The show ends with “La Chasse” (“The Hunt”) a monumental painting made much later, between 1938 and ’44, during another world war. I’m not sure why the curators included it here, but it seems to show Derain escaping into a Rousseau-like world of fantasy with its naively painted animals and alternative title: “The Golden Age, Paradise on Earth.”

The images on this page show the chameleon-like nature of this painter (an impression only reinforced by a visit to the aforementioned exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), who never stopped changing his style once the Golden Age of his Fauvist period ended.

By the time you reach the end of the exhibition, you can only agree with the statement made by Gertrude Stein, quoted at the beginning of the show, in which she speaks of him as a “discoverer,” “the Christopher Columbus” of modern art who didn’t know how to make use of his discoveries.

Favorite

Oops…I think you meant Christ’s Calvary, not Cavalry!

Thanks for catching that, Betsy.