Note to readers: You may choose to read this analysis of Émile Zola‘s Germinal here or listen to it on the audio file at the end of the article.

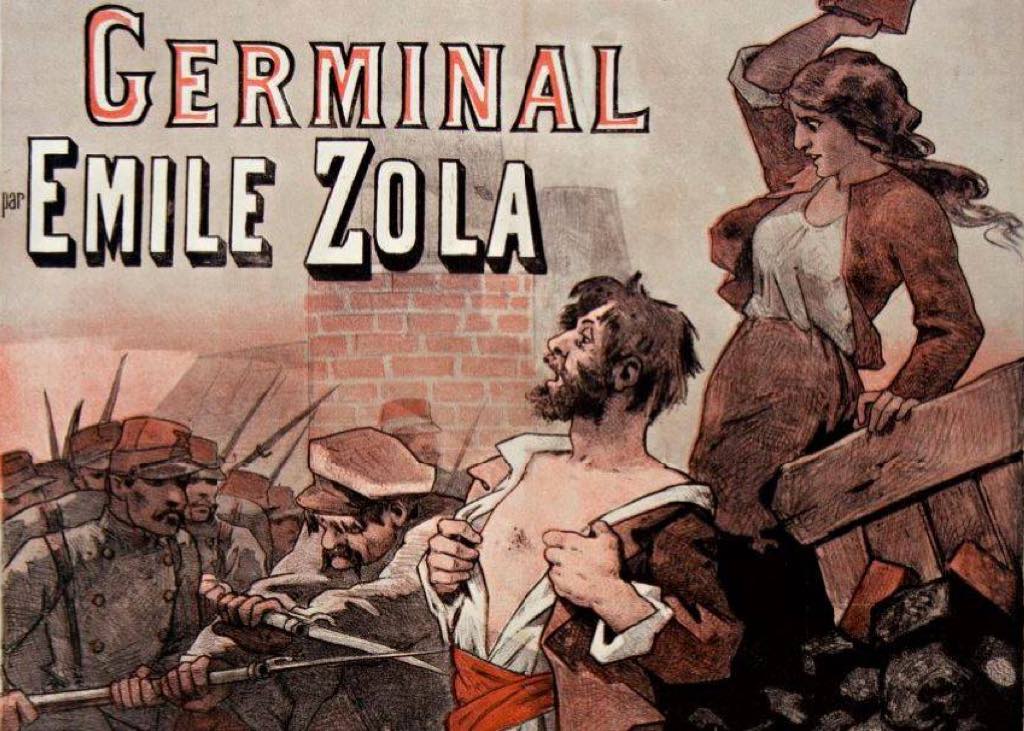

As a companion to last week’s discussion of Gustave Flaubert’s famous novel Madame Bovary, it seems appropriate to talk this week about a work by another 19th-century French novelist whose name is often placed beside Flaubert’s: Émile Zola.

Zola is perhaps best known for “J’Accuse!,” a public letter written in 1898 in defense of the imprisoned Alfred Dreyfus and condemning the anti-Semitism of the government of the day, but he was also the author of a monumental series of novels, “Les Rougon-Macquart,” in which he conceived a form of realistic writing known as naturalism, turning the novel into a scientific laboratory for the study of human behavior.

I must admit to having mixed feelings about the success or otherwise of Zola’s works. At their best, they are extraordinary feats of observation; at their worst, they seem to me little more than melodramatic forays into soft porn.

When the Marxist critic George Lukács writes of Zola that “perhaps no one has painted more colorfully and suggestively the outer trappings of modern life,” he is clearly damning the French writer with extremely faint praise, for he is suggesting that (unlike a writer like Thomas Hardy, who tries to understand the motivations and contradictions of his characters) Zola finds himself trapped within the “bombastic monumentalism” of the naturalist project.

In some respects, Lukács is as guilty as Zola in making overly sweeping brushstrokes in his analysis, for in a novel like L’Assommoir, one does have a sense of individual suffering and complexity within a broader study of alcoholism and poverty in an urban landscape. Also, in Nana, empathy for a woman forced into prostitution at times comes through more strongly than the wider aims of Zola’s quasi-scientific project.

The 13th novel in the series, Germinal, published in 1895, is unequivocally one of Zola’s greatest novels in its harsh depiction of miners’ strikes during the 1860s. I would argue that such “outer trappings” are essential to give a monumental but not bombastic sense of the crowd, of the seething mass of humanity that crushes the individual. Without such a macro-description – a broad overview – we cannot fully grasp the intensity of the individual’s micro-struggle against larger forces.

In this respect, the magnificent opening pages of the novel fulfill Zola’s desire to achieve this combination of micro and macro. While he researched and documented the mining industry of the time, giving precise details about the dimensions of mine shafts, machinery, tunneling techniques and working conditions to achieve a certain kind of realism, he was able in the opening to superimpose symbolic meaning on the as-yet-unnamed individual (whom we later learn is Étienne Lantier), who is swallowed up in a hallucinatory vision.

The novel begins with “a solitary figure” being consumed by “the murky waves of this world of shadows,” and it is this placing of the individual within a wider landscape that allows the reader to be mindful of the personal as well as the impersonal.

Lukács is perhaps justified in describing characters in Zola’s novels as “tiny, haphazard people,” but this is precisely the point Zola is trying to make at the beginning of Germinal. While the overarching symbolism in a later Zola novel like La Bête Humaine is both crass and verging on the pornographic, the monumentalism in Germinal is essential to both the structure and worldview of the book.

Although the documentary description in the novel is crucial, we should not forget that Zola makes use of much more traditional narrative techniques. Étienne, as the work’s central figure, plays an essential role in structuring the novel. There is symmetry in the way Étienne’s arrival at the beginning is matched by his departure at the end. The imagery of regeneration at the end of the novel (“the sap flowed upwards and spilled over in soft whispers”) shows that Zola was not averse to the beauty of both poetic and documentary description.

Moreover, a character like the fellow miner Bonnemort plays both a symbolic and narrative function in alerting Étienne (and the reader) to the history of many years of suffering and death in the mining industry: Bonnemort’s surname (literally meaning “good death”), which he acknowledges to be a nickname, is not a coincidence. Zola combines his customary physiological description of Bonnemort with symbolism: while he is said to have “a massive neck and bandy legs,” “long arms” and “square hands,” he is then compared to “a stone statue, seeming not to notice the cold,” a kind of monument to all miners who have become impervious to the hardship of their surroundings.

Bonnemort also is used as a narrative device to give the reader as much historical information as possible at an early stage of the novel, prompted by Étienne’s question, “Have you been working at the mine for long?” For all of Zola’s proclaimed new approach to literature, it is a remarkably clumsy and old-fashioned narrative device.

Perhaps the most arresting narrative technique is the way Étienne becomes a different kind of narrator/novelist himself. The stories he tells others show both the seductions and drawbacks of persuasive rhetoric. Although Étienne gets his facts mixed up and sometimes cannot find the right words, talking “endlessly, in increasingly passionate tones,” he is able to create new worlds and suggest the possibility of hope within the grim world that is depicted in the rest of the novel. Thus, although the wife of a fellow miner, known as La Maheude, tries to block her ears from Etienne’s own narrative, which she dismisses as “fairy-tales,” we find that “little by little the charm started to work on her too.”

We can perhaps most usefully see Zola’s own novelistic project in this light: could he have been employing his own brand of Flaubertian irony here, presaging the failure of his “scientific” project? For all its seeming objectivity, Germinal is memorable precisely for the seductiveness of its storytelling, the vividness of its imagery and the mythic status of its symbolism.

All quotations from Germinal are from the translation by Peter Collier (Oxford World’s Classics).

Favorite

Merci pour cette stream. Le site soi-même est jolie et informatif. Merci pour cela aussi. Aujourd’hui est l’anniversaire de l’acteur Gerard Depardieu donc je m’intéresse dans son film Germinal et je suis arrive chez votre site. J’espère avoir assez bien écrit, cela fait de nombreuses années que je n’ai pas utilisé mon français. Merci encore.