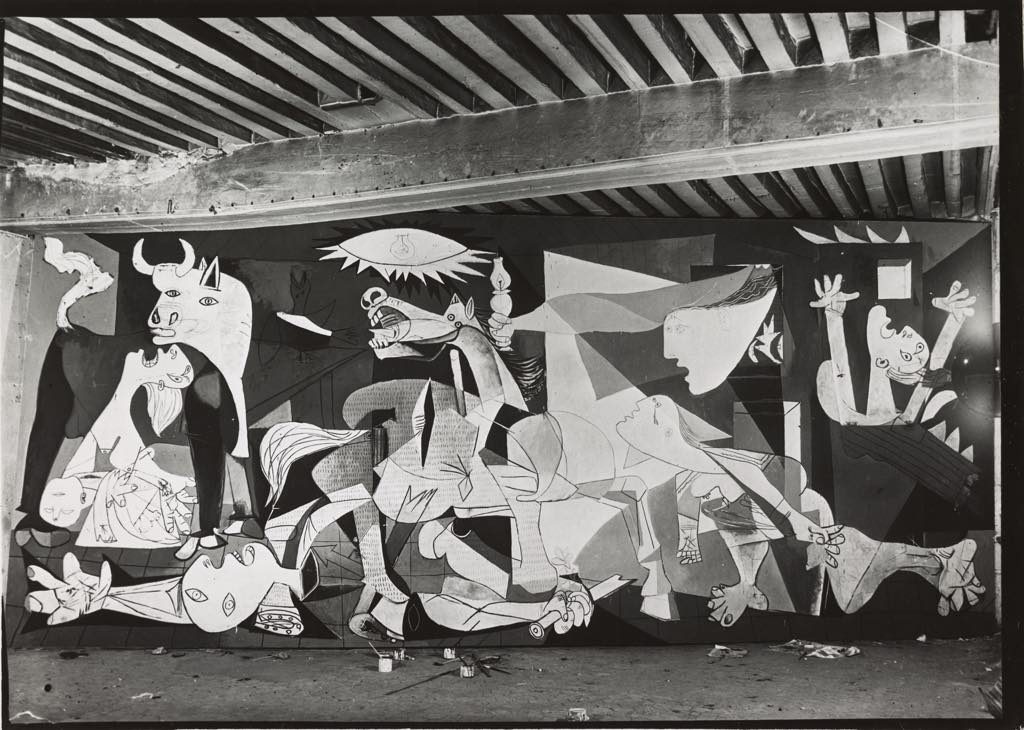

To celebrate the 80th anniversary of the painting of Picasso’s “Guernica,” Paris’s Picasso Museum has put together an absorbing exhibition that dissects the symbolism of the monumental work and explores in detail its genesis and influence.

“Guernica” was the Spanish-born artist’s famous protest against the evils of the Spanish Civil War, as represented by the devastation of the Basque village of Gernika by Nazi and Fascist bombs in April 1937.

The only thing missing from the exhibition is the painting itself, which now hangs permanently in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid after having traveled the world, basically homeless, ever since it was painted in Paris in 1937. Picasso refused to allow it to be shown in Spain until the Spanish Republic was restored. It was taken in by the Museum of Modern Art in New York until 1981, when it finally went to Spain.

The show starts out with a useful and interesting analysis of the painting’s iconography. A large reproduction is analyzed point by point and the interpretations of various commentators offered. Art historian Max Raphael, for example, said, “Picasso has drawn an electric light bulb inside the ‘bomb’ to suggest how readily a beneficial invention may be transformed into a destructive force in the modern world.” The woman carrying a lamp is variously seen as Nemesis, the Greek god of vengeance, and as a witness shedding light on the tragedy of Guernica for posterity, as the painting itself does.

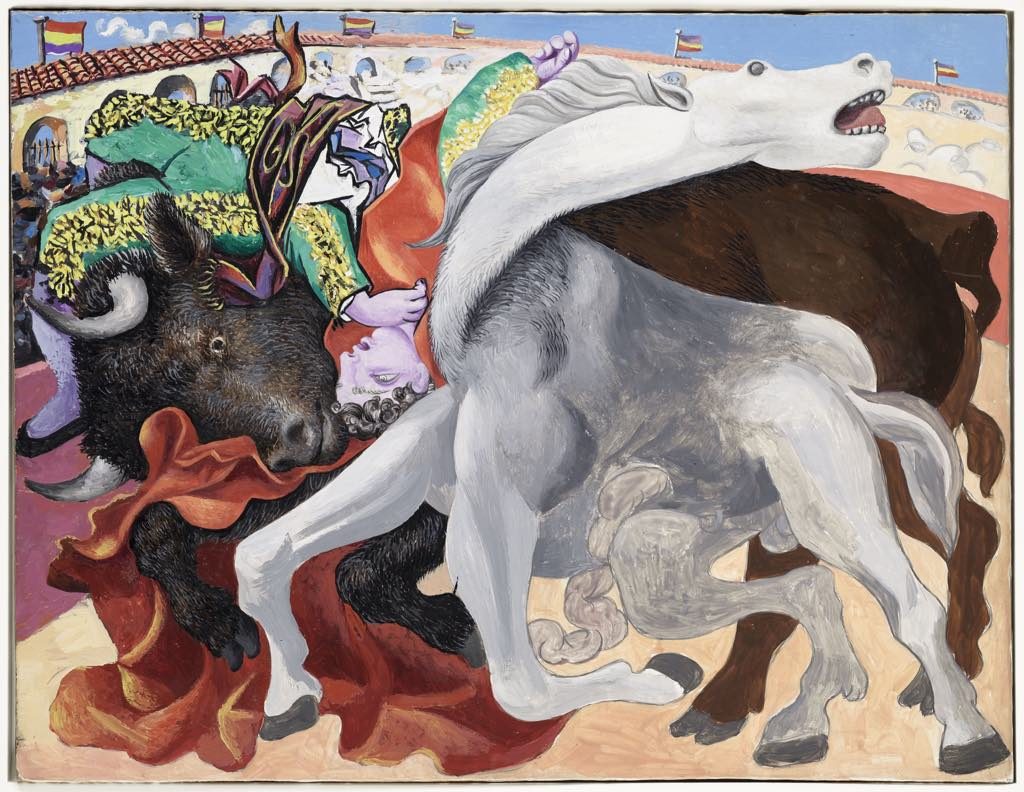

In 1945, Picasso said that the bull represented brutality and the horse the people, but in 1947 he refused to attribute meaning to them: “The bull is a bull. The horse is a horse. … They are slaughtered animals. That’s it. The public can see what they want in it.”

When Picasso became interested in a subject, he liked to get his teeth into it and investigate it thoroughly in drawing after drawing, as he did with his interpretations of Velásquez’s “Las Meninas” and Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe.” Just a few days after the bombing of Guernica, he started making the first of over 40 sketches for the painting.

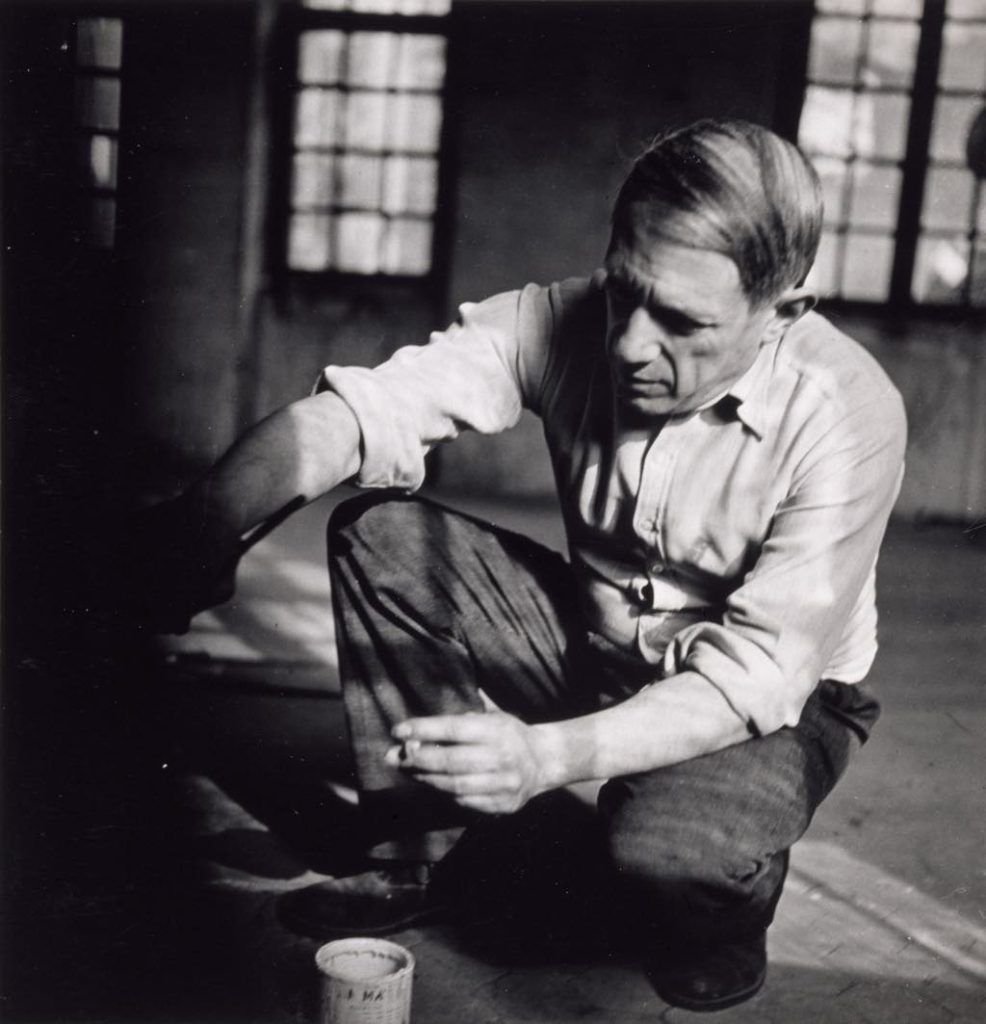

The painting itself was executed in record time between May 4 and June 10, 1937, in Picasso’s Left Bank studio on the Rue des Grands Augustins. Picasso’s progress on the painting was documented by his then-lover, photographer Dora Maar.

On show in the exhibition are many of the preparatory sketches as well as previous works that influenced “Guernica” and others he had already created before painting “Guernica” to express his outrage at the atrocities committed during the war, including the 1937 satirical etching “Songe et Mensonge de Franco” (“Dream and Lie of Franco”).

To set the scene, the show also presents the front pages of contemporary newspapers, posters and photos. A number of “Guernica”-inspired works by other artists wishing to express their opposition to Franco’s regime are on show, as well as Luis Buñuel’s controversial “documentary,” Land Without Bread, a sort of travelogue, much of it staged, that the Surrealist filmmaker shot in an impoverished region of Spain in 1933.

Favorite

Concerning Picasso’s stay in Paris during the war, see http://observer.com/1999/02/everybody-loves-picasso-even-critics-and-nazis/