|

|

|

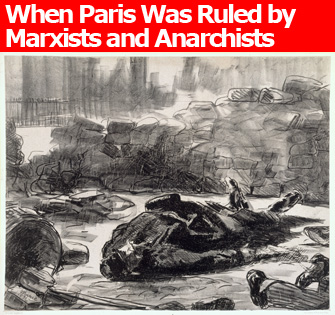

Édouard Manet’s “Guerre Civile” (1871) © Musée Carnavalet – Roger Viollet |

The Paris Commune, a euphoric workers’ uprising followed by a bloodbath, remains a mystery to most foreign visitors to the city. An exhibition at Paris’s Hôtel de Ville …

|

|

Édouard Manet’s “Guerre Civile” (1871) © Musée Carnavalet – Roger Viollet |

The Paris Commune, a euphoric workers’ uprising followed by a bloodbath, remains a mystery to most foreign visitors to the city. An exhibition at Paris’s Hôtel de Ville commemorating its 140th anniversary helps make the story clear.

The revolutionary government of the Paris Commune ruled Paris from March 28 to May 28, 1871, following the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. Paris refused to give up its guns following the surrender of Napoleon III to the Prussians, and the Parisian working class quickly took control of the city. For a short time, Paris was governed by Marxists and anarchists before the Commune was crushed by French regular forces led by Adolphe Thiers.

In the foreword to the exhibition, Paris’s mayor, Bertrand Delanoë, reminds us that the Commune helped promote “secularism, workers’ rights and the emancipation of women.” The show begins with exhibits that express the enthusiasm and the intellectual and political ferment during the Commune. Decrees were issued forbidding night work, for example, and giving free stationery to students. The Commune’s leaders, among them writer Jules Vallès and painter Gustave Courbet, were especially interested in bettering working conditions. Far from being excluded from the movement, women played a significant role in it, setting up a Women’s Union and campaigning for women’s rights. The anarchist and feminist Louise Michel, a schoolteacher who offered to shoot Thiers herself and is now an icon of the French left and a symbol of the labor movement, was the most famous of them.

One interesting piece is the diary of a Parisian hostile to the Commune. Her greatest fear is to be forced to house French National Guards, who constituted the core of the Commune’s military power. The entry on April 13 reads: “What a night! Impossible to sleep, I hear cannon fire.… Paris is ruled by bandits.” It is a shame that such exhibits are so scarce (there is only one other diary) as they show how ordinary Parisians lived though this unique experience and shed a new light on the Commune.

The show also focuses on the violence engendered by the crackdown on the Commune. During the infamous “Semaine Sanglante” (“Bloody Week”), from May 21 to 28, 1871, no fewer than 20,000 people were executed or killed in street fighting. The hatred engendered by the uprising led many “Communards,” as the Commune’s supporters were pejoratively dubbed, to be shot down in cold blood after they were taken prisoner.

Some of the most striking exhibits are those that show how Paris suffered from the uprising and its consequent suppression. Paris was so damaged that for more than 20 years, ruins were an ordinary sight for Parisians. Many buildings were burned down and, while some, like the Hôtel de Ville, were rebuilt, others were subsequently razed, among them the Tuileries Palace, the palace of the 19th-century French kings and emperors.

As in all wars, some opportunists managed to turn devastation into profit. A certain Mr. Hans published a “Guide à Travers les Ruines” (“Guide Through the Ruins”) for tourists. A 1871 engraving shows thrill-seeking foreign tourists visiting Paris’s ruins.

Ultimately, this exhibition is a useful reminder of the events that took place during one of the most turbulent periods in French history. The exhibits are interesting, but few of them will be new to those who are familiar with the events of the time. For those who would like to learn more about the Commune, the city of Paris is holding a series of eight lectures about it with scholars and historians through June 17.

Hôtel de Ville de Paris: 29, rue de Rivoli, 75004 Paris. Métro: Hôtel de Ville. Tel. 01 42 76 51 53. Open Monday-Saturday, 10am-7pm. Admission: free. Through May 28. http://bit.ly/eEgxaC

Reader Thirza Vallois* writes: “I read the article on the Commune by Louis Fraysse with great interest. I found it excellent and hope it will incite many readers to visit the exhibition. I also wrote a story about the Commune and the exhibition for another publication. I, however, perceive the episode as more tragic than fascinating. I happened to visit the exhibition the day of the Royal Wedding and was struck by the respectful silence in the venue in contrast with the excitement, the silly mugs, the Barbie dolls and the overall ‘buzz’ fed by the media. By the end of the weekend, the young couple was forgotten, pushed aside by Bin Laden.

The impact of the Commune on the likes of Karl Marx and later Mao Zedong cannot be overestimated, for beyond the humiliating surrender to the Prussians that gave rise to the Commune, it was the first manifestation of a proletarian uprising and a role model for future revolutions. The episode happened at a time of horrendous poverty all over Europe in the wake of the Industrial Revolution and was aggravated in the case of Paris by the burden of new taxes following the annexation of its suburbs in 1860. It was because of the proletarian threat that Prussia put a quick end to the occupation of Paris, thus allowing Thiers government to take control of the city. After all, the French and Prussian authorities may have been at war with one another, but they belonged to the same privileged class (during the French Revolution, the neighboring monarchies allied against the newborn nation for the same reason).

“I came out of the exhibition with a feeling of immense sadness. All the suffering, the wasted lives, the trampled hopes, the crushing defeat… Not that the Communards were blameless. As a matter of fact, they were the ones who started it by executing innocent hostages, including the Archbishop of Paris. But they killed in the dozens, while the Versaillais government troops massacred them in the tens of thousands. All in one week: men, women and children. The official figure quoted is usually 20,000, although some sources suggest much higher figures. Nobody really knows. That’s over and above the horrendous destruction, not just of the city’s main monuments, which were set afire to the despairing Communards, but entire chunks of street reduced to rubble by the troops’ bombing as they pushed their way east across the city coming from Versailles.

“The final fighting took place in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery, where the last Communards (also known as Fédérés) were dislodged tomb by tomb. Picked randomly, 147 of them, including women and youths, were lined up against the cemetery wall and shot by a firing squad. The wall, now known as Le Mur des Fédérés, has become the emblematic memorial of the Commune, the site of many left-wing commemorations. Six hundred thousand supporters of Léon Blum’s Front Populaire gathered here after their victory on May 24, 1936, soon to see their hopes shattered like those of the Communards.

*Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris and Aveyron – A Bridge to French Arcadia.

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Buy other music and books from the Paris Update store: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2010 Paris Update

Favorite