|

|

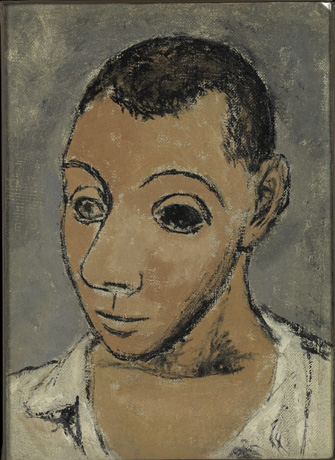

Paul Cézanne’s “La Femme de l’artiste dans un fauteuil (Madame Cézanne à l’Eventail)” (1878-88) © J.-P. Kuhn, ISEA Zurich. Picasso studied this painting at the Stein’s and noticed that one of the eyes was all black, a trick he borrowed for his self-portrait and other works. |

Aside from the many great artworks on show, the special interest of the exhibition “Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso: The Adventure of the Steins,” opening today at the Grand Palais, is the story it has to tell about some of the larger-than-life figures who helped create the still-fascinating legend that was Paris in the early 20th century.

The story of avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein is well known, but that of her family perhaps less so. It was Stein’s intellectual, art-loving brother, Leo Stein, who first called his sister to Paris. She came, she saw and she conquered, but not right away. First, she settled down with Leo in an atelier at 27, rue de Fleurus in 1903. They were followed to Paris by older brother Michael and his wife Sarah, who lived in the nearby Rue Madame. Without being filthy rich, all of the Steins were comfortable enough to not have to work and to be able to buy works of art.

But not just any works of art. The prices of one of their favorites, Paul Cézanne, were already spiraling out of reach, so they began to buy his works on paper and to acquire the work of some unknown young upstarts. Now, if I were to do the same thing today, I am pretty sure that in a hundred years’ time, my heirs would own a worthless piece of art. But when the Steins did it, they helped launch the careers of artists who made an indelible mark on the history of art: notably Matisse and Picasso.

Each section of the exhibition has a storytelling corner that sets the stage for the surrounding artworks with text, films, photos and publications (these fascinating but too-small spaces are going to be jam-packed with people trying to take in all that material). The story begins with Leo, whose interest in art started the whole “adventure.” Following his initial interest in Cézanne, he turned to Matisse and later Renoir. In this section of the show, we see some lovely lithographs by Cézanne (versions of his bathers, widely copied by other artists) and most notably Matisse’s “Woman in a Hat,” a shocker when first exhibited in 1905 with its

|

|

Matisse’s “Femme au Châpeau” (1905), which caused a scandal the first time it was shown. © Succession H. Matisse. Photo: Moma, San Francisco, 2011 |

violent Fauve colors, and “Nu Bleu: Souvenir de Biskra” (1907), equally scandalous when it was painted and a source of fascination to Picasso, a frequent visitor to Rue de Fleurus, who criticized it for its decorative qualities yet took inspiration from it for his “Demoiselles d’Avignon.”

It is striking how, after starting out so strongly as an early supporter of Picasso and Matisse, so avant-garde at the time, Leo later changed allegiance, getting rid of all his Matisses and concentrating on collecting the works of Renoir, which seems to me a great lapse in taste, as does – to a lesser extent – Gertrude’s later penchant for Picabia. Leo’s judgment was warped in other ways: Henri-Pierre Roché wrote that Leo believed that Picasso was an illustrator of genius and that he should do nothing but draw. And, revolted by Picasso’s Cubist works, he left the Picassos to Gertrude when they split their collection and took the Renoirs with him. All a matter of personal taste, I suppose.

Michael and Sarah, however, took up Matisse in a big way, collecting his work, becoming close friends with him and even encouraging him to open an art academy in Paris in 1908, which Sarah and Leo attended. In the next section of the show, we see the notebook in which she jotted down the master’s pearls of wisdom, among them “Order, above all (in color)” and “One must always search for the desire of the line.”

More importantly, we see an amazing large room full of the luminous colors of 25 Matisse paintings owned by the couple, plus drawings and sculptures by him, and a few works by Cézanne, Picasso and Henri Manguin. To my eye, many of Matisse’s paintings, sculptures and drawings are not convincing, but when they work, they are magical in their beauty and rightness. A few examples here: the Cézanne-influenced “Nature Morte à la Cruche Bleue” (1900-03), the early “Canal du Midi” (1898-99) and the marvelous still life “Les Oignons Roses” (1906-07), in which the sensuously plump pink onions contrast brilliantly with three patterned pitchers and a green and blue background.

Michael and Sarah lost many of their Matisse paintings after lending them to a German gallery for an exhibition just before the outbreak of World War I, then in 1935 they moved back to the United States, much to the chagrin of their friend Matisse.

Gertrude, however, stayed on. Three major events more or less coincided in her life: the installation of the now-legendary (thanks to Gertrude) Alice B. (“B” for Babette) Toklas at Rue de Fleurus in 1910; the completion of her monumental work, the critically panned The Making of Americans, in 1911; and the total break with her brother Leo, who moved out of their shared home in 1914, after disputes about Cubism, her homosexuality and oversized ego, and other matters, not necessarily in that order.

Many books have been written about the self-aggrandizing Gertrude and her world; the exhibition does not go deeply into her biography but instead concentrates on the artists she befriended and championed, notably Picasso, who debated questions of artistic philosophy with her and whose

|

|

The Picasso self-portrait (1906) with one black eye (see Cézanne painting above). © Succession Picasso 2011 |

Cubist experiments supposedly inspired her repetitive writing style in the “continuous present.”

Gertrude’s section of the show includes Picasso’s famed portrait of her, along with other portraits by such artists as Balthus, Tal-Coat, Jacques Lipchitz and Picabia, as well

|

|

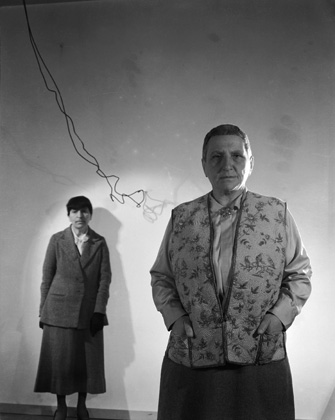

Cecil Beaton’s “Alice B. Toklas; Gertrude Stein” (1936). © Courtesy of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s |

as photos by Man Ray and Cecil Beaton (notably two in which Gertrude stands proudly in the foreground while Alice is reduced to a small figure in the background). There are also a number of Cubist works by Picasso and Juan Gris, including the most beautiful Cubist painting I have ever seen, Picasso’s colorful “Homme à la Guitare” (1913).

The many anecdotes about the lives of this out-of-the-ordinary family add a special zest to the show. A description of the Saturday evenings hosted by the Steins, buzzing with visitors come to see the paintings and meet the artists, for example, is enough to make you want to time-machine Woody Allen-style back to that moment. Mabel Dodge wrote that people mocked the art they had seen after leaving the Steins’ salon, not realizing how much they had been changed by it. And, she might have added, how the history of art would be changed by it.

Needless to say, this show is a must-see. Congratulations to the curators of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Grand Palais in Paris for tracking down all these works that once belonged to the prescient Steins and putting together such a magnificent exhibition.

Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais: 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008 Paris. Métro: Champs-Elysées Clemenceau. Tel.: 01 44 13 17 17. Open Friday-Monday, 9am-10pm; Tuesday, 9am-2pm; Wednesday, 10am-10pm; Thursday, 10am-8pm. Admission: €12. Through January 16, 2012. www.rmn.

Order the exhibition catalog from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: France, U.S.

Reader Jonathan Jacobs writes: “I enjoyed your review of the Stein exhibition, which I saw here in San Francisco. You had the same reaction to the show that I did and expressed it very well. I thought you covered it much better than Kenneth Baker, the San Francisco Chronicle art critic, who is usually quite good. The title of the show at SFMOMA was ‘The Steins Collect: Picasso, Matisse and the Paris Avant-Garde,’ and I would like to recommend the catalog by that name if you haven’t already read it. It adds a lot more material on the whole Stein family and is, unlike most catalogs, very well written.”

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2011 Paris Update

Favorite