The Light and Dark Sides of

A Beloved Artist

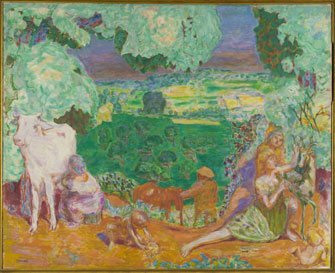

Pierre Bonnard’s “Vue du Cannet” (1927). © Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/ Patrice Schmidt © ADAGP, Paris 2015

Pierre Bonnard had a way with animals, winningly capturing their expressions and movements, most famously in “The White Cat” (1894, pictured below), but that was only one of the subjects that fascinated this painter of intimate interior scenes, vibrantly colored landscapes and much more. Guy Cogeval, president of the Musée d’Orsay, which is currently hosting the must-see exhibition “Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947): Painting Arcadia,” describes the artist as a “cat with seven lives.”

Art critics and historians, says Cogeval, who co-curated the show, have tended to write about Bonnard “as if he never changed; as if the man was the same person in 1900 as in

“The White Cat” (1894). © Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt © ADAGP, Paris 2015

1940. But he was not at all the same Bonnard. We know more about Bonnard today and can speak more freely about his personal life and its influence on his art. This is a new view of Bonnard.”

Bringing together 32 paintings from the Orsay’s collection and some 60 borrowed from other museums and private collections, as well as a trove of often-intimate photographs, the exhibition traces the arc of Bonnard’s life and career from avant-garde experimentalist in fin-de-siècle Paris to his death at his home near Cannes in 1947.

Divided into eight sections by theme, the show starts in 1890s Montmartre, where Bonnard, still a student, was a member of the Nabi group of Postimpressionist artists and a theatrical designer for Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, a satirical, surrealist play so scandalous for its time (1896) that it was forced to close after only one performance.

Right from the first four panels, “Femmes au

The four decorative panels that make up “Femmes au Jardin” (1890-91). © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski © ADAGP, Paris 2015

Jardin” (1890-91), the visitor is immersed in Bonnard’s world. Their virtuosity is striking in its modernism, and the influence of Japanese prints is clearly visible in flat planes of patterned cloth.

Bonnard has a unique way of framing his subjects, creating a multi-dimensional spatiality with strange perspectives and mirrored reflections. In the section titled “The Unexpected,” look out for hinted presences — an arm, a leg or a pipe barely visible at the edge of a painting. The margins serve both to define a space and to link it to its unseen context.

Another facet of the artist that stands out in this exhibition is his complex use of color. Because his aim was not to imitate life but to re-imagine it, he never painted directly from life – he would sketch and then return to his studio later to paint. The vividness of his palette reflects the vividness of his imagination.

One section of the show, titled “Clic-Clac Kodak,” presents photos of Bonnard and his friends, including pictures of the artist and his wife frolicking naked in the garden.

Bonnard’s life was not all fun and games, however. A key to a conflicted side of it can be seen in “Young Women in the Garden,” painted between 1921 and ’23, which shows a golden-haired young woman turning to look up at the artist from her chair by a table laden with fruit. Barely visible in a corner of the picture is a second, dark-haired, young woman, who is staring at the first.

The blonde is Renée Montchaty and the brunette is Marthe de Méligny (née Maria Boursin). Both were his models and both were his mistresses. When he finally married

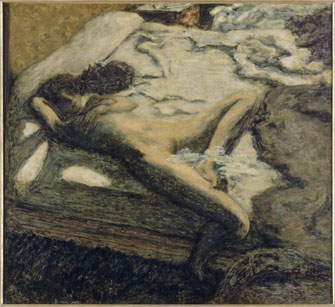

“Femme Assoupie sur un Lit” (1899). © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/Thierry Le Mage © ADAGP, Paris 2015

Marthe in 1925, after a 32-year relationship, Renée killed herself. Over the next two decades, Marthe turned into an obsessive recluse, spending hours every day washing herself and withdrawing almost totally from social life.

Some of the finest works in the show are paintings of Marthe bathing, which take up an entire room; apparently odes to tender intimacy, they hint at a darker story.

Musée d’Orsay: 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 75007 Paris. Métro: Solferino. RER: Musée d’Orsay. Tel.: 01 40 49 48 14. Open Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30 a.m.-6 p.m., until 9:45 p.m. on Thursday. Admission: €11. Through July 19, 2015. www.musee-orsay.fr

Reader reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2015 Paris Update

Favorite