Fans of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) are in for a real treat this summer, with the Musée d’Orsay in Paris featuring the artist’s portraits; the Fondation Pierre Gianadda in Martigny, Switzerland, holding a major exhibition of mostly landscapes, “Le Chant de la Terre” (to be reviewed here next week); and the Kunstmuseum Basel showing his drawings in “The Hidden Cézanne: From Sketchbook to Canvas.”

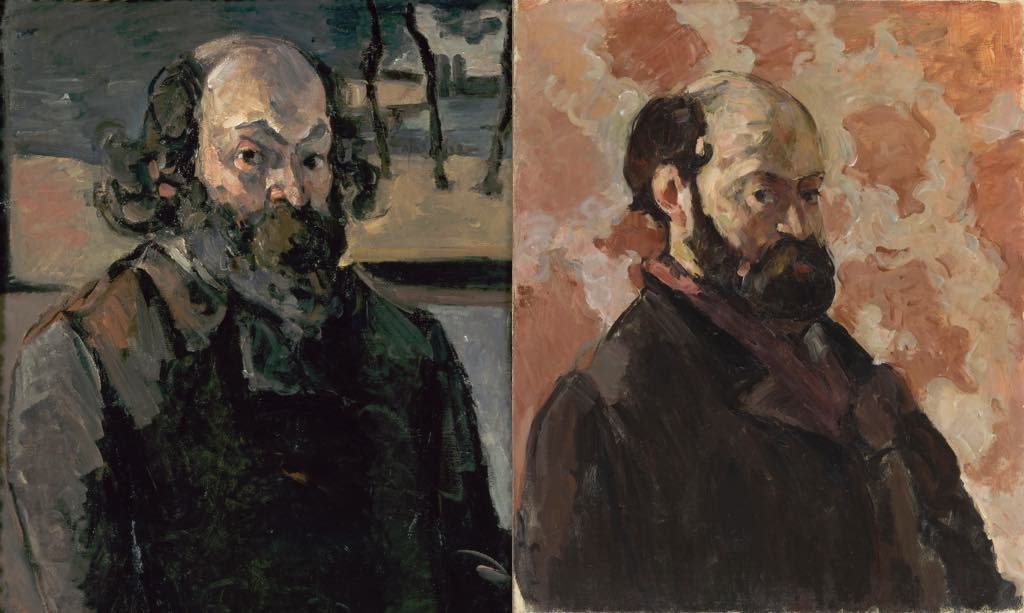

When we think of Cézanne, we tend to think of his sensual still lifes or luminous landscapes, but portraits accounted for over 150 of his overall output of around one thousand canvases. He was in the habit of painting with painstaking slowness, a luxury most artists of his day did not enjoy, since he didn’t have to worry about making a living thanks to an allowance and later a large inheritance from his father.

The show starts with early portraits, including a self-portrait showing a very intense, angry-looking young man with touches of fiery red in the corners of his eyes and on his lips. A rather touching portrait of his father, who did not approve of Cézanne’s decision to be an artist, shows him reading a newspaper, the name of which the artist changed, amusingly, from the conservative “Siècle” typical of his father’s taste, to that of the avant-garde “L’Evénément.”

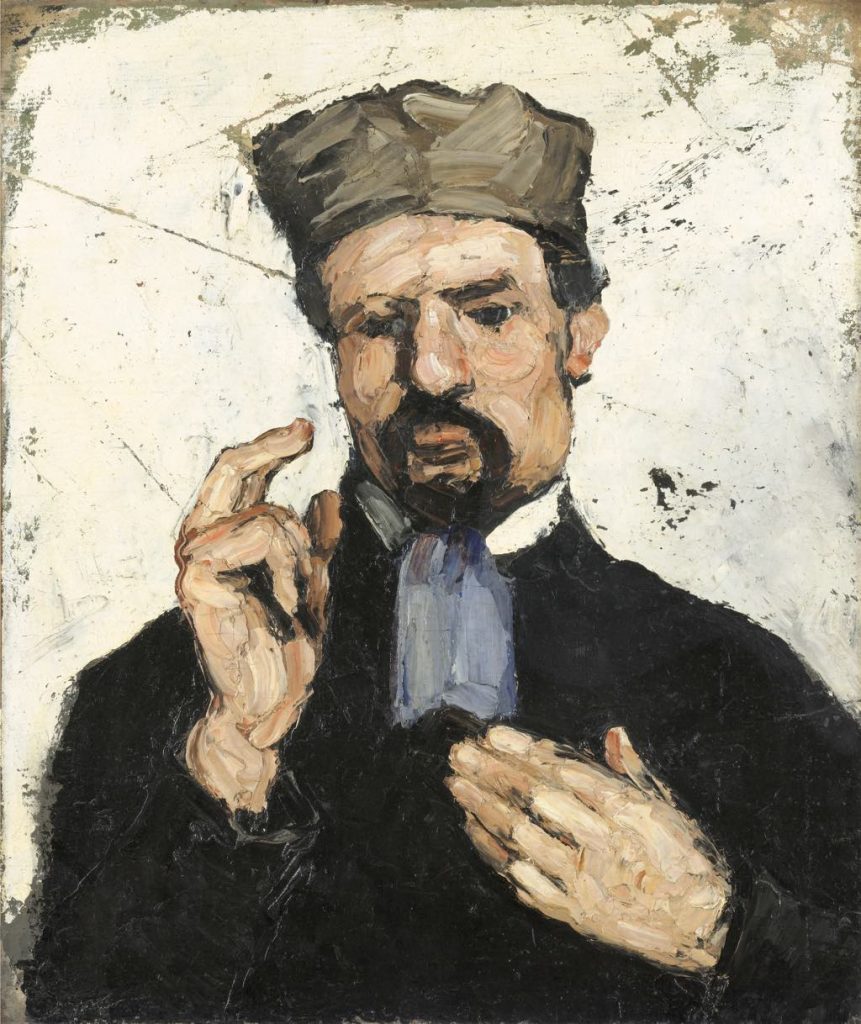

In an interesting series of portraits of his uncle, Dominique Aubert, the young artist daringly built up the image by slapping on layers of thick impasto. What he later called his “couillarde” (ballsy) period marked a turning point in his approach to painting as he moved away from traditional techniques and experimented with his own.

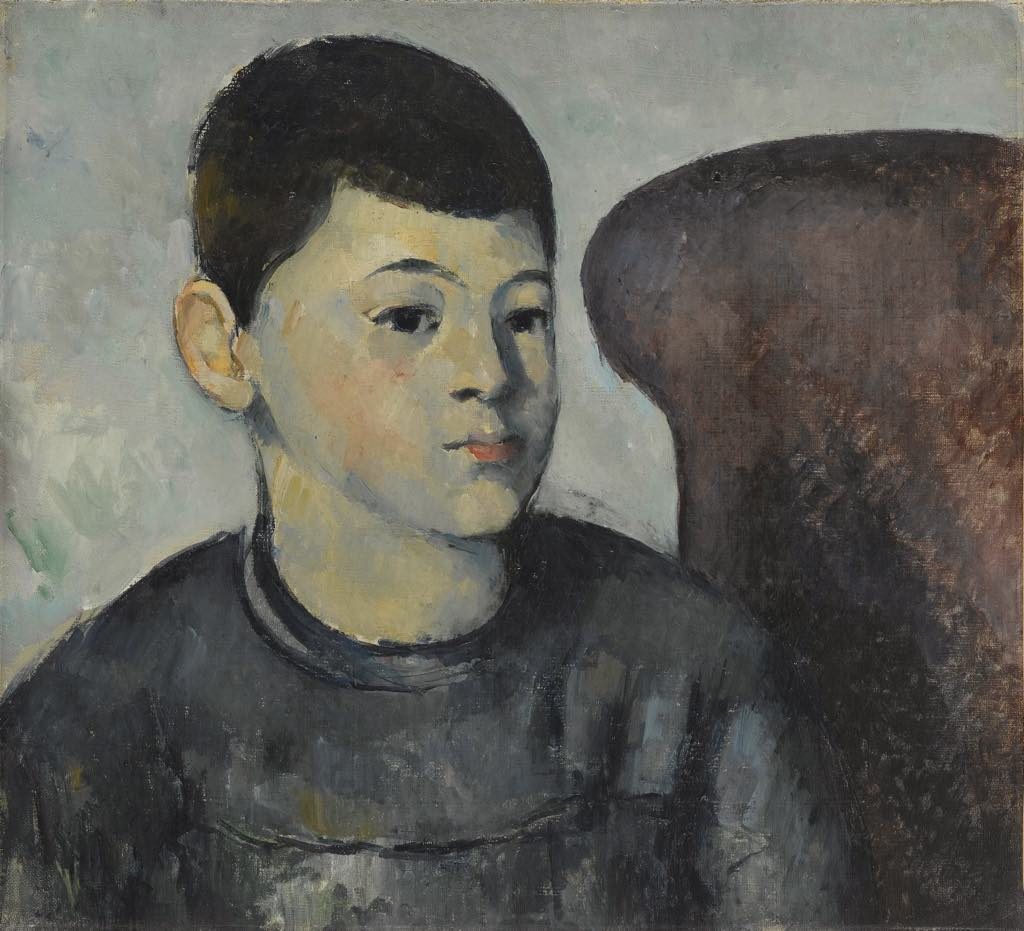

Cézanne painted what was near to hand and painted it over and over. He made 29 portraits of his wife Hortense Fiquet (the subject of the portrait on the left above), with whom he had a troubled relationship. Many interpretations have been made of her glum expression and dead-looking eyes in these paintings, but who knows – perhaps that was just her usual, at-rest expression.

When he painted the same subject many times, Cézanne was not trying to create a fair representation of what he saw but experimenting with building up forms through the use of color. The exhibition allows us to watch this process by presenting multiple images of the same subject, with 14 portraits of Hortense, five of them in the same red dress, and 11 self-portraits.

Cézanne was unique but hugely influential. The artist that Picasso and Matisse famously called “the father of us all” is credited with paving the way to the 20th century, bridging the gap between the old world of art and the new.

While he was associated with the Impressionists for a time and even studied under Camille Pissarro, he was not really one of them. He stubbornly went his own way in spite of the vicious critical ridicule his work attracted in the early years, but while he didn’t achieve success and start selling paintings until relatively late, he was always admired and even revered by other artists. It just took a while for the rest of the world to catch up.

Favorite

Will the Cézanne exhibit still be there on Sept. 20-22?

Thanks, Henry

Yes, it closes on Sept. 24 (the end date of the exhibition is marked in red under the show’s name on the upper righthand side of the page).