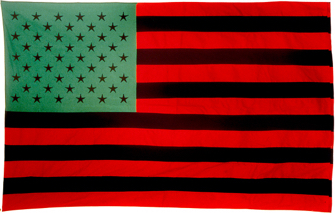

Paris seems to be taking a fresh interest in American culture. The musical comedy, an alien art form here, is now a staple at the Théâtre du Châtelet, where 42nd Street is currently packing them in, and the Musée de l’Orangerie is showing “American Painting in the 1930s: The Age of Anxiety.” Another source of anxiety in the United States, racism, is the subject of the exhibition “The Color Line” at the Musée du Quai Branly.

The show’s subtitle, “African-American Artists and Segregation,” is misleading. Most of this enormous, wide-ranging exhibition is a thoroughly documented historical look at racism, segregation and discrimination in the

United States, beginning with the post-Civil War Reconstruction period and continuing through the Black Power movement of the 1960s. While African-American artists are presented as part of this story, it is not until the end of the show that we see a goodly number of works by them.

The French already know a lot about American racism (far more than most Americans know about French history), so this exhibition will only confirm their dim view of the American record on the issue.

As an American, I already know a lot of this story – Jim Crow laws, lynchings and other forms of violence, blatant discrimination in every sphere of life and more – but there was still much to shock me. For example, I learned that President Andrew Johnson, Abraham Lincoln’s successor, vetoed the Civil Rights Act

of 1866, which went into effect anyway. This law made individuals born in United States citizens of the country, with the stunning exception of Native Americans.

On the grim subject of lynchings, it was sickening to discover that many were announced ahead of time in newspapers to give people time to get there to enjoy the spectacle. In one of several such newspaper reports reproduced in the show, Governor Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi explains that he is powerless to prevent the scheduled public burning of a black man accused of molesting a white woman. Thousands flocked to the town of Ellisville to watch.

Less serious but still shocking is the fact that as late as 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City could mount an exhibition called “Harlem on My Mind” without including a single African-American artist.

This exhaustive show – illustrated with photos, posters, books, music, film clips and much more – covers a plethora of subjects, including minstrel shows, with their blackface white performers; early battles against segregation waged by Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, and the work of the NAACP; the participation of segregated African-American regiments in World Wars I and II (another shocker: some WWI veterans were lynched after the war while wearing their uniforms); African-Americans in sports and entertainment; the Harlem Renaissance; race cinema; the migration of many southern African-Americans to the industrialized north (wonderfully illustrated by the then-23-year-old artist Jacob Lawrence [1917-2000] in “The Migration Series” paintings); and the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

Oliver W. Harrington’s sharp editorial cartoons provide comment on many of these developments.

Works by African-American artists are interspersed throughout the show, but the majority are presented at the end, giving long overdue attention to such names as (in addition to Lawrence, who is well represented here), Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), Horace Pippin (1888-1946), Archibald J. Motley, Jr. (1891-1981), Aaron Douglas (1899-1979), Romare Bearden (1911-88), Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), Norman Lewis (1909-79), Robert Thompson (1937-1966), David Hammons (born 1943), Mickalene Thomas (born 1971), Ellen Gallagher (born 1965), just some of the more than 50 on show.

For an American, visiting this exhibition is painful, especially at the moment when our first African-American president is leaving office and being replaced by a man whose stance on racism is, at best, ambiguous. Let’s hope that the gains that have been so hard-won – not only for African-Americans, but also for women and other minorites – won’t be lost in the coming four years.

Note: A small exhibition of paintings and stained-glass works by leading African-American artis Kehinde Wiley is on show at the Petit Palais through Jan. 15.

Reader Alison Culliford writes: “I re-read your review of this show after seeing it on Saturday, and really appreciated your personal reactions to the exhibition, skilfully interspersed with a very true representation of what to expect. The title was indeed misleading and your own title far more apt. Thanks for name-checking all those artists, who were a revelation to me. Thanks for choosing that portrait of the kindly faced victim of hatred, among so many powerful works. One of the exhibits that I thought most timely was the 1915 advertisement for the racist film Birth of a Nation – boasting about the outrageous budget and the number of jobs created by the making of the film. It could have been written by Trump himself. Also interesting to a non-American who has never fully understood the changing semantics (‘black’ being far less politicized a word in the UK, though it is now being replaced by the inclusive BAME) was the exhibit from the 1900 Paris Exposition compiled by W.E.B Du Bois that included hundreds of photographs of African-Americans and statistics to illustrate their diversity: it showed the word ‘African-American’ has a long and noble history. Anyone wanting to know more about the continuing failure of the United States to live up to its promises of freedom should watch the documentary 13th, currently on Netflix.”

Favorite