|

|

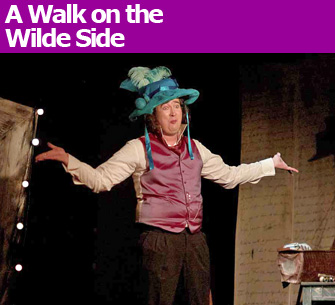

Nikola Carton gives an exceptional performance as a man who thinks he is the reincarnation of Wilde. |

Last week, I saw the star-studded A Little Night Music by the legendary Stephen Sondheim at the sold-out Théâtre du Châtelet and a one-man show called Une Fable sans Importance, ou …

|

|

Nikola Carton gives an exceptional performance as a man who thinks he is the reincarnation of Wilde. |

Last week, I saw the star-studded A Little Night Music by the legendary Stephen Sondheim at the sold-out Théâtre du Châtelet and a one-man show called Une Fable sans Importance, ou L’Importance d’Etre Oscar Wilde in a tiny theater on a side street in Montmartre.

Guess which I enjoyed more.

Yes, of course I preferred the homage to Oscar Wilde, written by Charles Decroix, who also scored the music, and staged by Clémence Weill.

But I owe a warmly enjoyable evening in the depth of winter as much to Nikola Carton, who gives an exceptional performance in Une Fable.

For just over an hour, Carton demonstrates a sure mastery of the theatrical craft as he plays a character who has been told he is the reincarnation of Oscar Wilde. Although the story is a little on the light side, the skilful verve of the impersonation sweeps the audience along in this Wildean evocation.

We are treated to mime, an extended dramatic monologue, full-throated song, a little dance and an on-stage pause to eat a banana, which prompted appreciative hilarity from the young woman in front of me, who threw her head back in loud laughter.

A delightful piano accompaniment and a walk-on part for the scarlet-clad Hélène Bizieau add to the theatrical touches.

The play draws on Wilde’s work and life to juggle a number of ideas: personal identity, destiny, rising above mediocrity and love.

Oh yes, love, in part the undoing of the Irish writer who has probably gifted the English language with the greatest number of quotable quotes after the Bible and Shakespeare.

Carton’s character delivers a homily on love between men and women. Friendship between men and women is simply not possible, he emphatically tells us – passion, yes; dislike, yes; but friendship, no.

There may be a love between men and women who are also friends, I venture to suggest, and today this is the love which dares not speak its name.

As if the intelligence, sympathetic insight and wit of Wilde’s writing were not enough to ensure enduring appreciation, the way he lived, loved and died add vivid color to the portrait of the artist who loved deeply and maybe unwisely.

The fatal flaw that led him to sue his accuser for libel – the Marquess of Queensbury called him out in insulting terms on his homosexuality – makes him a tragic character in the tradition of Classical Greek theater.

But that downfall led to De Profundis, the work he wrote after his two years in the hell of Reading Gaol. It revealed Wilde’s spiritual depth, a world away from the aphorisms of short-lived social glitter. In the writing, he gave meaning to his suffering, showing his true mark as an artist.

In De Profundis he transformed the darkness of a brutal prison existence into the light of abundance: “When you really want love, you will find it waiting,” he wrote.

In his work and life, he spanned Comedy and Tragedy, the two forms of Classical drama. That surely explains why Wilde continues to fascinate.

The British film director Brian Gilbert turned out a touching biopic, Oscar Wilde, in 1998, and Oliver Parker’s film Dorian Gray opened in Britain last year.

Paris, of course, holds a special place in Wilde’s story. He fled to France after his fall from grace in Britain. He lodged in penury and died at the Hotel Alsace (now L’Hôtel), and he is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery.

It is surely one of the wonders of the French cultural scene that plays can be written and staged in small neighborhood venues like the Théâtre Funambule-Montmartre. The cast and audience are in close contact in these little places, reminding me of student theater workshops, during which an actor might say to the audience, “We’ll be back in 15 minutes if you want to meet and talk.” That keeps culture alive.

Wilde knew the A-list splendors of the Théâtre du Châtelet, but he also came to know how the other half lives.

Théâtre Funambule de Montmartre: 53 rue des Saules, 75018 Paris. Métro : Lamarck-Caulaincourt. Tel.: 01 42 23 88 83. Thursday-Saturday at 8pm, Sunday at 6pm. Through March 21. Tickets: €20 (reduced rate: €13). www.funambule-montmartre.com

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Buy related books and films from the Paris Update store.

© 2009 Paris Update

Favorite