I have written about the Caillebotte estate in the town of Yerres several times, extolling its many virtues: it is located only half an hour from Paris, and it boasts a large, beautiful park with a number of follies, including a tiny chapel, an ice house and a river with boats for rent; a handsome, recently restored 19-century manor house that once belonged to the family of Gustave Caillebotte; a sizable kitchen garden; and a good restaurant. All that makes it a perfect outing from Paris, but that’s not all: it also holds excellent art exhibitions. The two that are on now are worth a trip on their own, even without all those other attractions.

One of them, “Boris Zaborov: Peindre la Mémoire” (through September 21) features an artist I had never heard of who has a fascinating history and a style of painting all his own. As the show’s curator, Pascal Bonafoux, who knew Zaborov well, puts it, the artist “lived two lives.” Born in Minsk in the U.S.S.R. in 1935, he studied art but then found himself unable to conform to the codes of official Soviet art and suffered the humiliation of not being allowed to paint. Instead, he earned his living as a book illustrator, but was still harassed by the KGB because his drawings were seen as critiques of the regime. “I was filled with despair, exasperation and finally the fear of losing myself forever.” he wrote. His wife, Irina Bassova, a poet who still lives in Paris, was the daughter of the poet Boris Kornilov, who was assassinated on Stalin’s orders in 1938 during the Great Purge, and a friend of Dmitri Shostakovich, who had his own troubles with the Soviet authorities.

Zaborov managed to leave the U.S.S.R. with his family in 1981 and moved to Paris, where he plunged into painting, working 16 hours a day, and was soon exhibiting in galleries. Like Balthus, he forged his own style and belonged to no movement. His memories of his life before Paris are captured in otherworldly paintings based on old family photographs, which allowed him to conjure up a lost world with ghostly images that often seem to be disappearing into the material of the paint, opening “a door onto the silent world of people who have long since passed away” and giving “them a new life, an identity,” he wrote.

Keep an eye out for shadowy intruders in his paintings. In “Nora Nude in Profile with a Black Hat” (2007), for example, a young girl, posing stiffly and wearing a tutu, is barely visible standing next to the portrait of a large-breasted woman.

The themes of many of his paintings – childhood, family, death and animals – maintained his links to his native country and his lost life there: a loving family of artists, a little brother who had died suddenly at the age of six, a stray dog he adopted that had to be left behind when the artist and his family left Minsk. This affinity for dogs, whom he considered to be more highly evolved than humans, is evident in two paintings, “The Dog” (2012), a portrait of the lost pet looking yearningly at the viewer, and “Promenade” (2001), depicting a woman leaning against a Labrador. “He painted things that slept in his heart,” says Bonafoux.

The exhibition contains his most important works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints. The sculptures include a series of books in bronze, sometimes associated with another object, e.g., a broken doll, a watch, a compass or metal typesetting letters. Was he thinking that a book in bronze is not as easy to burn as one made of paper?

The ghostly figures in the paintings may have belonged to Zabarov, but you are sure to leave feeling moved, even haunted yourself, by his unsparing memories of his past. An online catalog offers a panorama of his works.

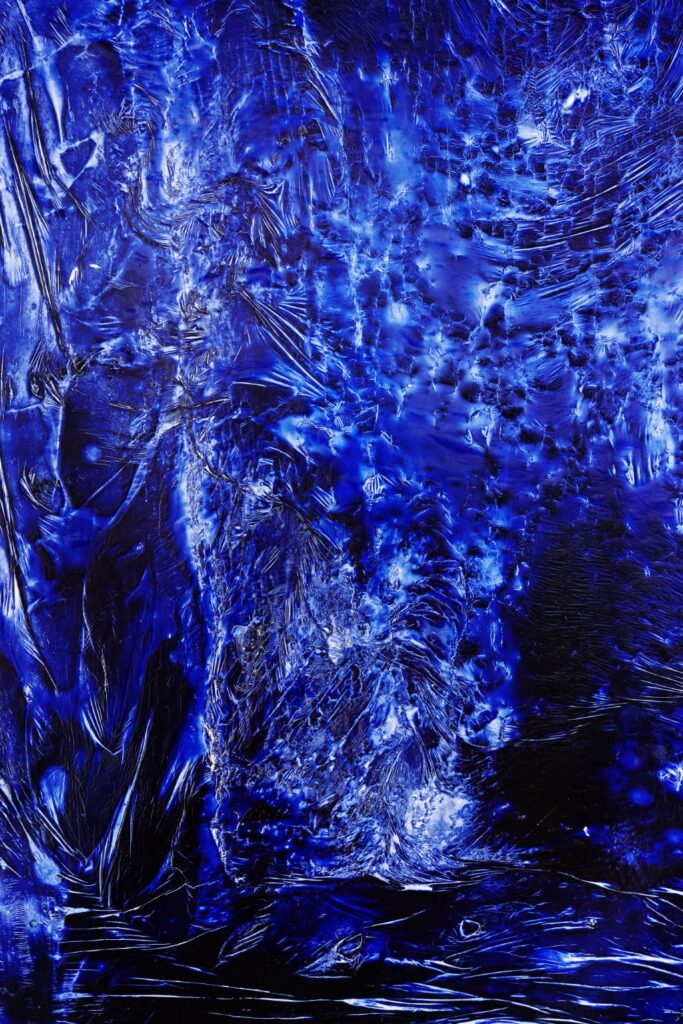

The other exhibition, on show in the estate’s Orangerie, “Evi Keller: Matière-Lumière” (through August 31), is an entirely different matter, although it also conjures up a sort of dreamworld. The beautiful large-format abstract paintings by the contemporary artist draw the viewer into a cosmic world of light and depth.

Keller has a mystical side that informs her work. “I am trying to penetrate the mystery of light,” she said at the opening of her show. “I’m an instrument of nature. Over time, I create a universe that moves toward us. Nature reveals itself in me.”

The paintings, which she considers to be more like sculptures, are made with a complicated technique that involves many layers of superimposed materials (pigments, minerals, plants, ash, ink and varnish), on which she then draws, paints, engraves, scratches, erases, sculpts and sometimes burns, exposing them to sunlight, rain and wind, or covering them with earth. The result is these huge works with complex patterns, all in intense blue, white and black.

!["Matière-Lumière [Towards the Light–Silent Transformations] n° 4831," by Evi Keller. © Evi Keller, Courtesy Jeanne Bucher Jaeger, Paris-Lisbon](https://www.parisupdate.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ParisUpdate-EVI_KELLER_TTL_MG_4831_portfolio.jpg)

Her photos, also very beautiful and made with complex processes, are from a series called “Towards the Light–Silent Transformations.” They depict mysterious, blurry forests that beckon the viewer into their shadowy world.

If you decide to take a break from Paris by visiting the Caillebotte estate this summer, make sure not to miss these two shows.

Favorite

I was moved by this article, by learning of Zaborov and seeing his wonderful, and as the author put it, haunting works. They hit me before I read the words related to them, and then the words hit me, too. I was taken aback by both paintings of the dogs. The colors I think are what make the paitnings strong, the subjects are sort of disappearing within them but are still front and center and meant to be seen and felt for. The dog in “The Dog” looks sad, he looks left behind. One can tell that Zaborov loved dogs and that they meant a lot to him, even before reading the article. Then to read how Zaborov adopted and then had to leave his dog behind, that made me sad and made the painting more meaningful still. The poor thing, I hope someone else took him in all those years ago. How difficult that must have been for Zaborov, clearly he wasn’t able to let it go and the loss affected him during his life. I wish I could see Zaborov’s exhibit, I won’t be in Paris until October. I will have to learn more about him now. Bonafaux put it exquisetly when he spoke of Zaborov painting things that slept in his heart. And to title the article with that line was also well done, it’s a great title. And don’t we all have things that sleep in our hearts.

Evi Keller’s art is quite extrodinary as well. It was interesting to learn the processs she uses to create her works — are they technically paintings after all. What an intricate method, you don’t hear of artists going to such lengths every day. Her creations are intense, I like them.

Thank you for your comments, Cory!