Smooth Surfaces,

Seething Undercurrents

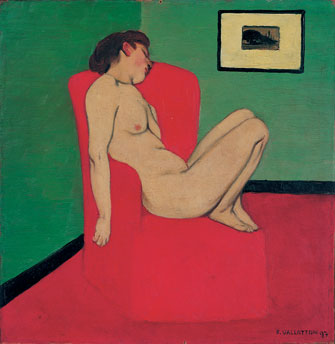

“Femme Nue Assise dans un Fauteuil Rouge” (1897), by Félix Vallotton. © Rmn-Grand Palais/Jacques L’Hoir/Jean Popovitch

How refreshing it is to discover an artist whose work you haven’t already seen over and over, especially when it is as interesting as that of Félix Vallotton (1865-1925). Although I was familiar with a few of his better-known paintings and some of his woodcuts, the large body of work by this Swiss-born French artist was otherwise unknown to me, and I suspect to many other visitors to the exhibition “Félix Vallotton: Fire under Ice” at the Grand Palais in Paris.

The show’s subtitle is apt; on the surface, his paintings have a tight, controlled, flat look to them, but apparently Vallotton was a troubled man whose childhood traumas and love/hate feelings for women seethed beneath the surface, creating a tension that is visible in his works. With their otherworldly feel, they sometimes reminded me of the paintings of Edward Hopper, although I cannot say that they are quite as eerie, and I think that Vallotton is a better painter than Hopper.

This surprisingly versatile artist went his own way. Except for a brief association with the Nabis, he was more or less oblivious to the artistic trends of his time, a quality you have to admire. He occasionally allowed his usually dulled-down palette to burst into vibrant color, as in “Femme Nue Assise dans un Fauteuil Rouge” (1897; pictured above), but even then an uneasy tension reigned; in this case, the woman’s tortured position and the bloody red of the chair offset what might in other contexts seem like cheery colors.

At their best, his works are beautiful and mysterious, as in the stark “La Loge de Théâtre, le Monsieur et la Dame” (1909), in which we see just the heads (and a white-gloved hand) of a woman in a big hat and a man behind her sitting in the shadows, shielded by a yellow wall that takes up nearly half the painting and cuts through it obliquely. The rest is darkness.

The exhibition is arranged by theme rather than chronologically, with rooms devoted to such categories as “Idealism and the Purity of Line,” “Flattened Perspectives,” “Icy Eroticism” and “Repression and Lies,” some referring to technical aspects of the work and others to psychological states of the artist.

“Repression and Lies” features a series of interior scenes full of menace. “Le Dîner, Effet de Lampe” (1899), for example, shows a family dinner harshly lit by lamplight. A man yawns, and a woman looks reprovingly at a little girl while the ominous black silhouette of another man – apparently Vallotton himself – looms over them all. This is not a dinner party one would want to attend.

Other interior scenes represent the relationship between men and women in a rather unflattering light, with the men depicted as dupes of calculating females, an attitude that was supposedly the result of the many heartbreaks the artist had experienced.

His versatility can also be seen in the juxtaposition of some of these paintings. An almost hyperrealist work might hang next to a nearly abstract one, and some have a surreal feel, like “Persée Tuant le Dragon” (1910), in which a tightly muscled Perseus shows no emotion at all as he kills the crocodile-like dragon, while a naked, unchained Andromeda, squatting on the beach, looks on in disgust; the scene takes place against the backdrop of a sickly greenish-pink sky. This painting was much ridiculed when it was first shown at the Salon d’Automne.

Vallotton’s compositions can sometimes be quite daring, as in the Lautrec-like “La Valse,”

“La Valse” (1893). © MuMa, Le Havre/photo Florian Kleinefennin which the hazy dancers seem to float in the air while the ecstatic face of a young woman pops up in the lower right corner of the painting. The landscapes have a dreamy quality and sometimes border on abstraction, as in “Coucher de Soleil, Mer Haute Gris-bleu” (1911), and many of the still lifes are appealing, among them “Poivrons Rouges” and “Dame Jeanne et Caisse” (1925), with its gleaming glass and metal contrasting with rough boards. His painterly skill is also clear in such works as “Etude de Fesses” (c. 1884), in which the model’s rear-end cellulite is unsparingly portrayed.

A psychiatrist could have a field day with Vallotton’s work, but we ordinary visitors can just enjoy it for its mystery, technique and occasional flashes of brilliance.

Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais: 3, avenue du Général Eisenhower, 75008 Paris. Métro: Champs-Elysées Clemenceau. Tel.: 01 44 13 17 17. Open Wednesday-Monday, 10am-8pm, until 10pm on Wednesday; Sunday-Monday, 10am-8pm (exceptions: through Nov. 1, and Dec. 21-Jan.4, open until 10pm daily except Tuesday). Closed Tuesday and December 25. Admission: €12. Through January 20, 2014. www.grandpalais.fr

Click here to read all of this week’s new articles on the Paris Update home page.

Reader reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Please support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

To order the catalog from this exhibition: click here: U.K., France, U.S.

More reviews of Paris art shows.

© 2013 Paris Update

Favorite