A couple of hours by Eurostar from Paris, two essentially French art shows in London offer an excuse for a weekend immersed in the Anglo-Gallic love-hate relationship. And, if you’ve time to spare for a long weekend, a day trip into the country could rewardingly take in a third.

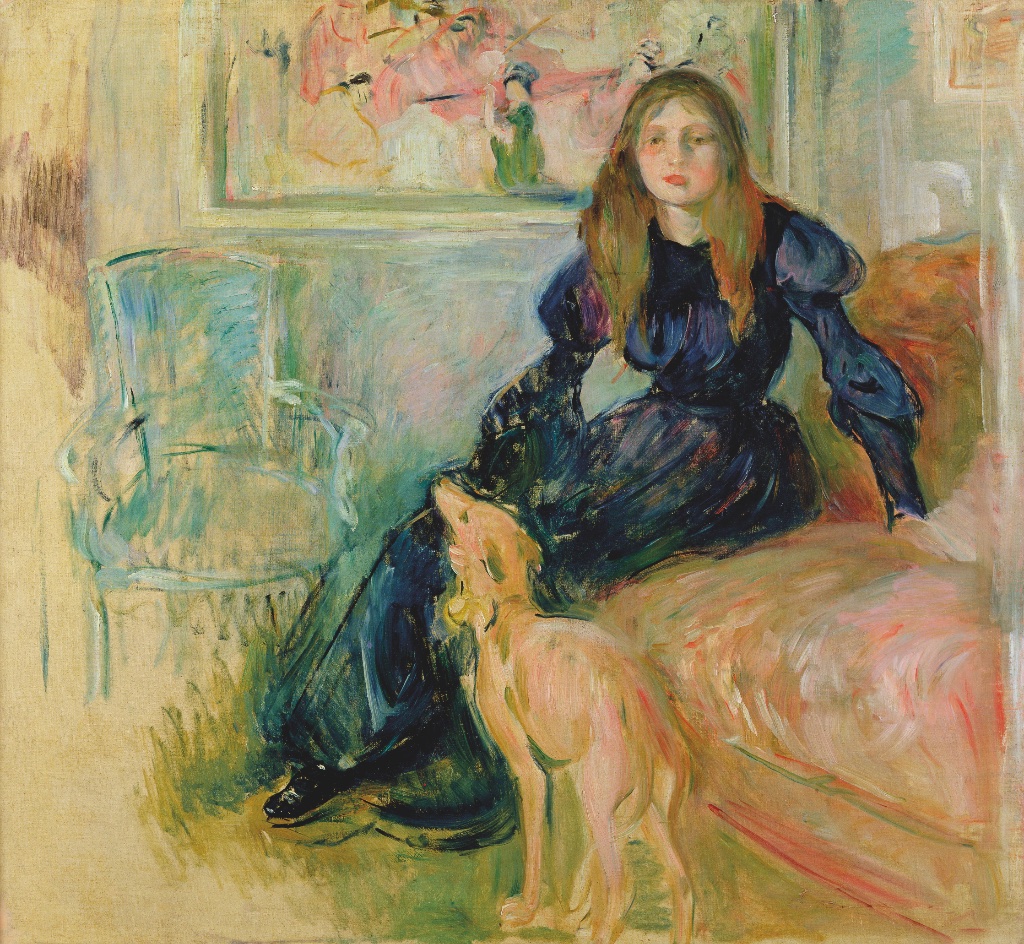

At the Dulwich Picture Gallery, housed in a Regency villa amid leafy South London parks, “Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism” (through Sept. 10. 2023) spotlights an often-overlooked Belle Epoque painter who helped to free French 19th-century art from the dead hand of academic neoclassicism.

At the National Gallery, in the heart of the capital, “After Impressionism, Inventing Modern Art” (through Aug. 13. 2023), takes forward the narrative from the last Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in 1886 to the outbreak of the First World War. A blockbuster exhibition of more than 100 works by over 50 artists, it illustrates the spread and metamorphosis of the artistic revolution from Paris across early 20th-century Europe to Secessionist Vienna, Berlin, Brussels, Barcelona and beyond.

A 90-minute train ride from London, “Gwen John, Art and Life in Paris and London” (through Oct. 8. 2023) at Pallant House Gallery, in the pretty south-coast cathedral city of Chichester, brings out of the shadows a painter long hidden behind her famous brother, Augustus John, and illustrious lover, Rodin.

The National Gallery exhibition is an impressive display of institutional heft, calling in loans from museums and private collections worldwide together with its own works, in a sort of Reader’s Digest canter through art’s great and good, plus a rich sprinkling of less-known but still striking works by Bonnard, Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Klimt, Matisse, Mondrian, Munch, Picasso, Rousseau, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vuillard and so on. Think of a name from A to Z, or a style from Pointillism to Expressionism to Cubism, and you’ll probably find it here.

Still, there are some notable gaps, not least a scarcity of women: just five of the 50-odd artists, with only one work on show for each, compared with five or six by several of the big male beasts. True, female artists had a hard time breaking through the male-chauvinist barriers of the time, but that’s no reason for carrying on the sexist tradition now. Happily, the Dulwich and Pallant House exhibitions can do something to plug the gap.

Born a generation apart on opposite sides of the Anglo-Gallic divide, Morisot (1841-1895) and John (1876-1939) were poles apart in their lifestyles and art, but some things they had in common, not least that both were written out of art history until recently by the mostly male keepers of the canon.

Morisot was a high-society cultural insider, daughter of an affluent top French government official, married to the seriously wealthy brother of the Impressionist pioneer Edouard Manet. John, daughter of a Welsh provincial solicitor, was an outsider, unmarried, subsisting on a modest inheritance, nude modeling and, later in her career, a small stipend from an American collector. Though both lived most of their lives in Paris, Morisot’s evolved in the elegant villas of Passy and the 16th-arrondissement, John’s in the bohemian studios of Montparnasse and the cloistered calm of suburban Meudon.

In an age when ladies sketched and colored as a leisure pastime, both were dedicated painters. Morisot studied under Corot and immersed herself in the 18th-century Enlightenment artists Boucher, Watteau and Fragonard. She showed in the official Paris Salon and later with the avant-garde Impressionist Salon des Refusés. (She also exhibited in London, with frustrating results: English art critics dismissed her as a dabbler who didn’t know how to paint properly. Morisot dismissed them as stuck-up and dull.)

John was a pupil at the Slade in London (the only art school in England that accepted females), studied under Whistler in Paris and took part in prestigious exhibitions, including the Autumn Salon in Paris and the Armory in New York.

Morisot’s painting is all about color and light, captured in swift brushstrokes and luminous, subtle tones. Her portraits of family and friends, and her scenes of social life – balls, strolls in the Bois de Boulogne, children at play, royal regatta week at Cowes in Britain’s Isle of Wight – captured moments of a privileged world that disappeared 20 years after her death, in the maelstrom of World War I.

Where Morisot painted a vivid social world, John painted inner stillness and solitude: A young woman reading, a nun, the absence present in an empty room. Purged of animation and drained of color – she followed Whistler’s dictum “black is the fundamental color of tonal harmony” – her paintings achieve a profound emotional intensity.

A Catholic convert in middle age, as her passionate 10-year relationship with Rodin was ending, she turned to an increasingly religious and reclusive life, fading from public view.

In 1939, on a visit to Dieppe at the outset of World War II, she collapsed, died and was buried in a local cemetery. For many years, the precise location of her grave was unknown, partly because many were dug up and reused three years later to bury the dead of the botched precursor of the Normandy invasion known as the Dieppe raid.

Since 2014 a plaque has marked the presumed spot. But true to form, it’s not certain she’s there.

See our list of Current & Upcoming Exhibitions to find out what else is happening in the Paris art world.

Favorite

Hi – Dulwich Art Gallery is not a villa, but designed as an art gallery by the great John Soane.

Hi Peter,

Good point — I used the word villa a bit loosely to indicate a certain scale. It was of course England’s first purpose-built public art gallery. But that’s a separate architectural and historical story, not the one I was trying to tell here. Thanks for being the proverbial sharp-eyed reader.