The exhibition “Edvard Munch: A Poem of Life, Love and Death” at the Musée d’Orsay does not start off with the Norwegian artist’s most famous painting, “The Scream,” but a sense of strangeness and unease still hits the visitor right away. After a couple of rather stiff early portraits of the artist’s sister Inger, visitors come upon “Self-portrait with Cigarette” (1895), painted around the same time, which tells a very different story: Munch (1863-1944) stands peering out at the viewer with rabbity eyes, as if he has just been startled by the bright light illuminating his face and right hand, which holds the lit cigarette. Most of his body is invisible, obscured by a sickly miasma of daubed-on blues, grays and grayish-reds.

This much-analyzed painting (its Wikipedia page offers a good summary), which was seen at the time as a sign of Munch’s social deviancy and mental health issues, sets the tone for the rest of this retrospective, which covers the artist’s 60-year career. The painting “Self-Portrait in Hell” (1903), shown at the end of the exhibition, in which the naked artist stands amid the fires of hell, is a terrifying echo of the 1895 work.

Munch is another artist who puts his life – especially his anguish and obsessions – into his work (see last week’s review of the Frida Kahlo exhibition), and the man who wanted to paint “people who are alive, who breathe and feel, suffer and love” makes no bones about it. He spelled that out clearly in the titles of many of his works: “Despair,” “The Sick Child,” etc. By accepting and not seeking to hide his mental illness – he once said, “My sufferings are part of myself and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art” – he contributed to the belief that artists and insanity are inextricably linked.

Certainly, two of the sources of the anguish he freely admitted to in his writings were the death of his mother when he was five (no paintings on this subject are included in the exhibition although they do exist) and his 15-year-old sister Sophie when he was 13. Was the latter the inspiration for the disturbing painting “Puberty” (1894-95)? It depicts a naked girl sitting on a bed, her body tightly clenched, staring defiantly at the viewer, with her threatening black shadow looming large against the wall off to the right.

There would seem to be little doubt that “The Sick Child” (1896) – depicting a scene witnessed while Munch was accompanying his father, who was a doctor, on a visit to a patient – refers to Sophie’s death, a theme that cropped up often in the work of the artist, who liked to repeat and rework his favorite subjects. This painting caused a scandal when it was exhibited in public, as did so many of the works in the show.

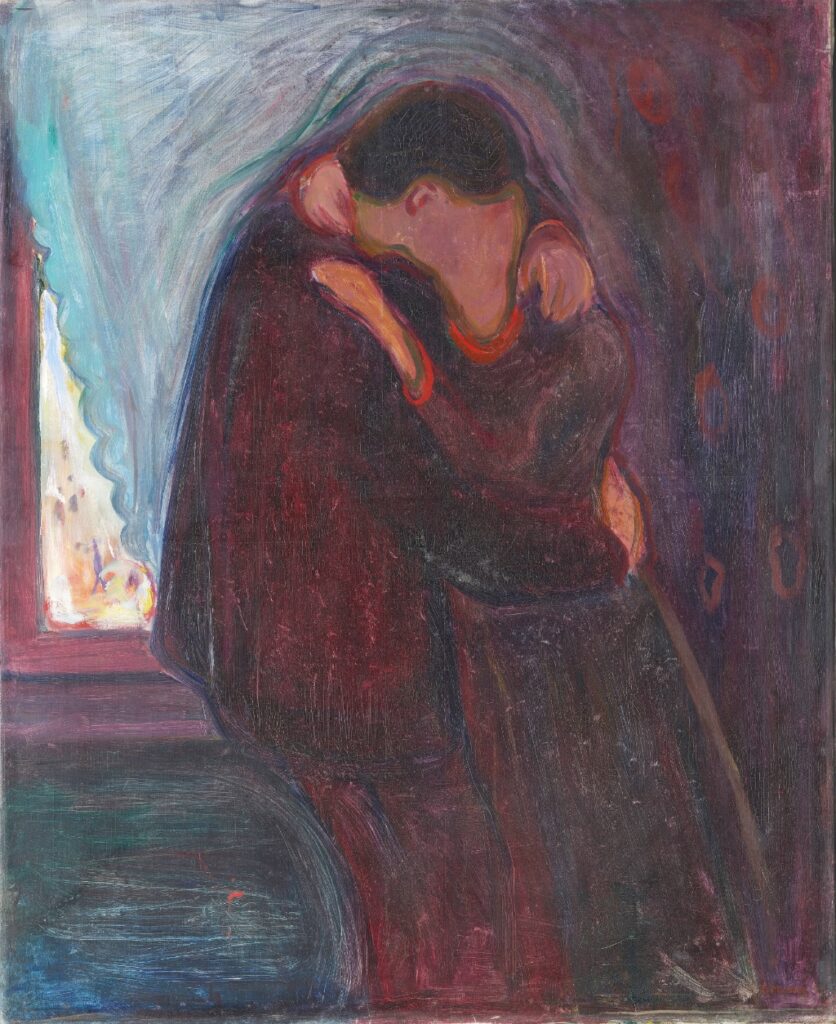

Another topic that obsessed him and that is manifested in a disturbing way in his paintings is love. The French use the word “fusionnel” to describe a relationship in which the emotional connection between two people is so intense that they cannot do without each other. Munch’s painting “The Kiss” (1897) is the perfect illustration of such a relationship: the faces of the two kissing individuals are literally fused together, enough to make anyone feel queasy. This theme, too, is repeated in many works, as is the related theme of vampires.

The few paintings here that do not emit despair and/or anxiety through both their subject matter and sickly colors are commissioned works like the frieze Munch painted for his patron, Dr. Max Linde, as decorations for his children’s bedroom. While it is obvious that Munch made an effort to make them cheerful and bright, Linde rejected them (but continued to support the artist). The exhibition includes one painting from this frieze, “Dance on the Beach” (1904), in which the large figures in the foreground stand perfectly rigid and look straight ahead with a walking-dead stare while smaller, less-detailed figures pirouette on the dance floor behind them. Dr. Linde’s reaction is understandable.

For those who know Munch mainly through “The Scream” (two versions of which are on show here), the exhibition offers a deeper look at the work of the artist and helps explain where that scream came from. What you see may not be beautiful, but it certainly is fascinating.

See our list of Current & Upcoming Exhibitions to find out what else is happening in the Paris art world.

Favorite