Back to Black:

A Global Retrospective

“Great Black Music” is a great big term that could encompass an awful lot of music, and the exhibition of the same name at Paris’s Cité de la Musique does just that, going out of its way to ensure that visitors enjoy themselves along the way

Rather than taking a strictly pedagogical or chronological approach, beginning in Africa and moving forward into the New World, the show jumps right into the music itself. As soon as they arrive, visitors are equipped with high-quality Audio-Technica headphones. The first room of this popular exhibition is crowded with shadowy headphoned figures hunched

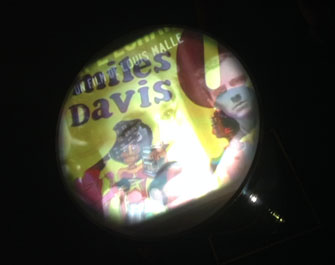

A documentary on Miles Davis being shown on a post in the exhibition.

over waist-high posts in the dark watching videos shown on the flat, round tops of the posts. Each video is a four- or five-minute documentary on a different artist, ranging from Nigerian Fela Kuti to Elvis Presley (whose presence is justified by the influence of black music on his style) and including Billie Holiday, Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Bob Marley, Miles Davis, Miriam Makebe,

James Brown and so on. The choice seems arbitrary, but the selection offers something for all visitors, whether they want to re-experience an old favorite (where was Otis Redding, by the way?) or learn about an unfamiliar artist. The little documentaries give equal attention to the music and the context of the artist’s life, with a strong emphasis on politics and the effects of racism where appropriate.

That room alone, where visitors could easily spend a couple of hours, might be enough for many, but the show goes on, with many more documentaries, presented in different ways, about roots in different parts of Africa and offshoots in other parts of the world, from salsa and reggae in the Caribbean, to rap and hip-hop, southern blues, Chicago blues, you name it.

There are three exceptions to the filmed documentary presentations: a display of black-and-white photographs taken in New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina, featuring the city’s musical street culture, by American photographer Lewis Watts; some musical instruments from Africa and the Americas; and lots of interactive games, jukeboxes and videos for kids and adults, including booths where visitors can film themselves learning a dance from a video.

The show, while certainly entertaining, seems fragmented. Maybe the curator found the subject too vast and gave up on trying to explain coherently the origins and many branching developments of “great black

music,” a term borrowed from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, which used it in the 1960s to describe this “invented tradition.”

The best explanation of black music I found in the exhibition was this: “It is impossible to draw a clean line between any of the forms of black music and ‘pure and authentic’ African music forms. Yet the various musical currents of the African diaspora do have points in common: a particular use of short melodic and rhythmic patterns that make you want to get up and dance (the riff in blues, funk and afrobeat, the loop in hip-hop), a clear penchant for rhythmic structures that emphasize a bar‘s off beat (syncopation, backbeat), the call and response technique, pentatonic scales, modified timbres that could already be heard in African instruments, which would become ‘dirty notes’ in American music (the gravelly voice of bluesmen, the mute and wah-wah of jazz trumpets, the saturation of electric guitars, etc.).”

This text also explains the functional dimension of black music, which was “intimately tied to the daily life of the communities that forged it,” as opposed to classical European music, which follows the “art for art’s sake” path.

I can understand why the curator, Marc Benaiche, director of Mondomix (“a magazine of world music and cultures”), didn’t want to be too earnest and academic, but a little more clarity and assistance in untangling the threads of this fascinating and complex subject would have been appreciated.

Cité de la Musique: 221, avenue Jean-Jaurès, 75019 Paris. Métro: Porte de Pantin. Tel.: 01 44 84 44 84. Open Tuesday-Thursday, noon-6pm, Friday Saturday noon-10pm, Sunday, 10am-6pm. Admission: €9. Through August 24. citedelamusique.fr/greatblackmusic

Click here to read all of this week’s new articles on the Paris Update home page.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

© 2014 Paris Update

Favorite