One of the things that make Paris a paragon of urban beauty is the way the Seine is incorporated into the municipal landscape. The Seine, of course, is the river that runs through the heart of the city, dividing it into the Right Bank and the Left (or, if you live on the Right Bank, wrong) Bank.

Many people have trouble remembering which bank is which. It’s actually quite easy if you just keep this little mnemonic in mind:

If you’re standing in front of Notre Dame Cathedral facing the main entrance, when you look to your left a pickpocket will snatch your wallet out of your right hip pocket. Watch which way he runs. That will be the Left Bank.

But what makes the Seine an integral part of the scene in Paris is that it is lined for its entire course through town with fine-masonry stone retaining walls, walkways and esplanades.

The purpose of all this infrastructure, built over many years at tremendous cost, is both aesthetic and practical. It makes the river easily accessible as a public space while at the same time making sure that the Seine doesn’t erode the surrounding real estate. It’s money in the bank, both literally and figuratively.

Actually, the channel work is not only to prevent erosion of the banks, but also to ensure that the Seine has banks in the first place. It is, after all, a river, and for that reason it rises and falls. And sometimes rises and rises. And rises.

Consider this inscription carved into a building on Place Maubert, at the corner of Rue Maître Albert:

It’s nearly illegible for a reason: the writing on the wall is more than 300 years old, from 1711 (the date is faintly visible toward the top) and commemorates a high-water event that brought the Seine up to about low-thigh level in that neighborhood. Not high enough to make the men’s wigs frizzy, but posing a definite threat to the contents of their snuffboxes.

The archives mention other severe floods in Paris in 866, 1206 and 1658, but Ze Beeg One, as no sane person ever calls it, took place in 1910. After a long period of heavy precipitation, the Seine started rising on January 20 of that year, and eight days later reached a height never before seen.

By the end of the month, some 20,000 buildings were flooded and about a third of the city’s streets were under water. Which kind of, sort of tended to pose some problems for transportation, not to mention the supply of drinking water, gas, electricity and food.

And wine. The Bercy district lies lower and further upstream than any other part of Paris, which meant that it was the first to be drenched by the deluge. Today Bercy is home to the Ministry of Finance and a stadium with grass-covered walls that I’m glad I don’t have to mow, but in those days it was the largest wholesale wine distribution center in Paris, no doubt in France and quite possibly in the world.

In row after row of warehouses, barrel after barrel of wine was lofted by the roiling water and swept away. Not surprisingly, the merchants of the Bercy district reported staggering losses due to the flood.

And, even less surprisingly, the towns downstream also reported staggering. Not staggering losses, just a lot of staggering.

Contrary to what one might expect, the flood was not a bank crisis: the water in the streets was not overflow from the river but backflow from the clogged-up sewers and filled-up Métro tunnels.

The Métro was only 10 years old at the time and had no flood barriers (as it does now) (or so they tell us), and the pressure of the high water had essentially turned its low-elevation tunnels and passageways into giant fire hoses, spewing out a constant stream of water, no doubt laced with discarded tickets, cigarette butts and accordions.

With the sewers returning their contents to whence they came, meat and vegetables rotting in waterlogged storerooms and a total breakdown of garbage removal services, Paris was soon blanketed with both a shallow lake and an off-putting stench — although in those days of horse power and pissoirs I’m not sure if anyone noticed.

What Parisians definitely did notice was an off-putting number of looters breaking into evacuated buildings. Several near-lynchings were reported as mob rule largely took over from the police, whose hampered movements, interrupted communications and lack of dry socks made it very difficult to maintain order.

By the time the water began receding on January 29, central Paris had been transformed into a cold, inhospitable, lawless, odiferous, contagion-bearing cesspool. On the bright side, people who didn’t have plumbing in their apartments no longer had to go down the hallway to the toilet.

The Seine didn’t return to its normal level until mid-March. There were relatively few deaths due to the flood, but the cleanup effort took months, not to mention the Herculean tasks of restoring utility lines, rebuilding buildings with damaged foundations, repaving streets full of sinkholes and wringing out sodden can-can skirts.

Fortunately, this type of circumstance is exceedingly rare. In fact, it’s called the “crue centenaire,” the “centenary high water,” because statistically it can be expected to occur only once every hundred years or so.

The key words here are “or so.” I’m no mathematician, but I’m sure that everyone will agree with me on the accuracy of the following formula:

2013 – 1910 > 100.

In other words, like an asteroid collision or the eruption of the Yellowstone Supervolcano, odds are we’re in for it pretty soon. Which is why I felt a little frisson of anxiety when I was walking along the Seine two weeks ago and, just upstream from the Pont des Arts, saw this:

It’s hard to discern in the photo, but the water was right at the edge of the walkway, and sloshing over it in the wake of any sizable boat.

Obviously, it was time to go see a guy in baggy kneepants. I refer, of course, to the statue of the Zouave that adorns one of the pillars of the Pont de l’Alma.

The Zouaves were French infantry soldiers in special regiments, deployed between 1830 and 1960, whose uniform consisted of a soft cap, a bolero jacket, spats and voluminous red trousers that made them look like they had gone directly from a costume party to the Crimean War.

Official measurements of the water level in the Seine are now taken at Pont Neuf, but unofficial assessments have traditionally been based on how much Zouave is visible above the waves.

The folk wisdom is that if the old bloomer boy’s boots are soaked, the river is getting dangerously high, and they close the Seine to boat traffic when the current reaches his calves.

Wondering whether a new wet-knickers contest had begun, I went last weekend to have a look. And here’s what I found:

Fortunately, for the moment the Zouave is under more snow than water. By comparison, in 1910 he was up to his lower lip in frigid, murky, garbage- and sewage-laden liquid muck. An experience that I personally hope to avoid. So I checked the maps of the areas affected by la grande inondation.

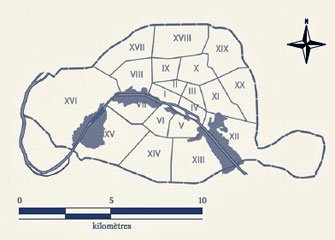

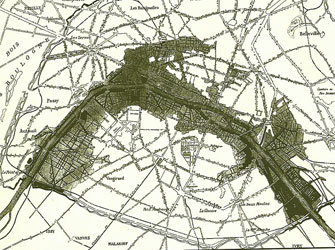

Interestingly, despite the fact that the catastrophe took place in the 20th century, well after the invention of photography and the introduction of at least moderately careful record-keeping, opinions seem to differ as to what parts of town were actually under water. According to one map…

… my district, the 9th arrondissement, was high and dry. But according to another one…

… there was an extra fjord of flooding in the north that came riiiiiiight to the doorstep of my building.

Obviously, it was time to go look for blue rectangles. In the districts near the Seine, you can see little metal plaques on the walls of some buildings marking the 1910 high water mark. This one…

… is on the Ile de la Cité behind Notre Dame. It’s about nostril-high, but fortunately far from my living room. This one, on the other hand…

… is only about five blocks away.

Granted, it’s low to the ground. So it’s too early to invest in hip waders just yet. But if I see that Zouave getting a fish pedicure next week, I’m moving to a houseboat — just west of Bercy. If the Ministry of Finance floods and the vaults break open, I want to be waiting with a net when the stuff starts floating downstream.

Note: For an actual historical account of the Great Paris Flood, with facts and stuff like that, I recommend Paris Under Water, by Jeffrey H. Jackson, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

© 2013 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.