Paris has an amazing lineup of exhibitions this fall. Among the most exciting are “Mark Rothko” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, “Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months” at the Musée d’Orsay, “Nicolas de Staẽl” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, and “Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit” at the Bourse de Commerce-Pinault Collection. Oddly enough, each of these four artists committed suicide. What that says about the theory that artists and other creative people tend to suffer from mental disorders, I don’t pretend to know (here’s an interesting article on the subject), but it does seem a strange coincidence.

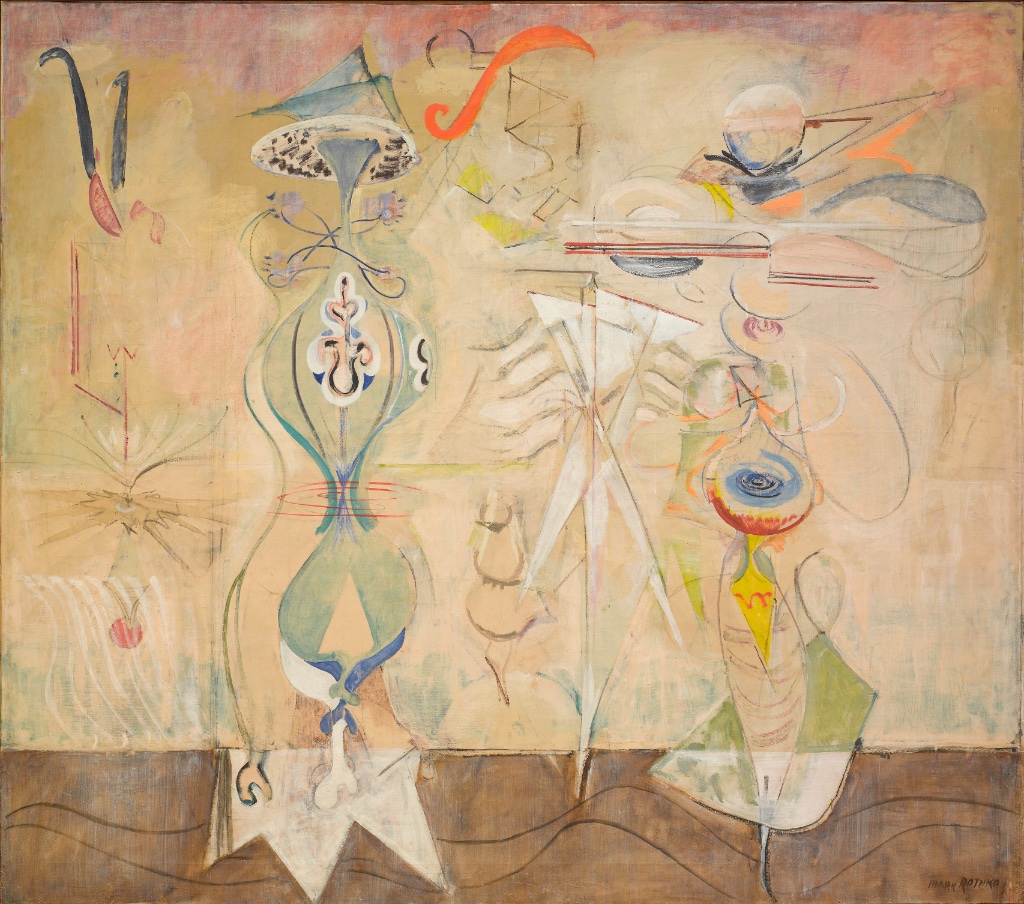

I was excited about seeing the Rothko retrospective in Paris after having fallen in love with his paintings at an excellent exhibition of his late works at the Tate Modern in London in 2008. Unlike that show, this exhibition, being a retrospective, begins with Rothko’s early figurative, mythological and Surrealist works, most of which, especially the figurative ones, with their oddly distorted figures and drab colors, make you glad that he turned to pure abstraction in 1940. Some of them, however, are affecting, such as the subway scenes, with their simplified figures and architectural forms.

The show then takes us through the development of his abstract works. Recognizable forms begin to dissolve into blobs of color that eventually take shape as rectangles and squares, and gradually become the floating superposed horizontal rectangles immediately identifiable as Rothko paintings.

Early on, the carefully built layers of color were mostly bright and intense, often with dramatic contrasts between them. While Rothko claimed that he was not interested in color but in light, it is the interactions of the colors in the juxtaposed blocks of carefully built-up layers of paint that fascinate us as viewers and draw us into the depths of … we don’t know exactly what. It’s almost as if the artist has performed an act of magic, which may not work in every piece, but packs a powerful pull when it does, sparking not emotion exactly but something close to it.

Some believe that the paintings have a calming or meditative effect, and the quieter ones certainly do, but Rothko denied any intention of creating peaceful works. “I have imprisoned the most utter violence in every square inch of their surface,” he once said.

Gallery 9 of the exhibition offers examples of that “violence” – a sort of struggle between the colors underneath and the predominant ones on top (especially in the contrasting blue and red or orange). The apparent serenity of pieces like “Blue and Gray” (1962), which has a calming, meditative effect at first glance, disappears when you look at it for any length of time (necessary to appreciate all of these works); you then see the stormy effect of the black background under the dominant patch of white.

As time wore on, the colors became darker and muddier. For this show, the Tate Modern has lent the paintings that live in its Rothko Room, nine of the works commissioned for (but never delivered to) the Four Seasons restaurant in Philip Johnson’s Seagram Building in New York City. These works marked a turning point in Rothko’s work, deviating from the usual floating rectangular fields of color with what might look like portholes or windows.

Another famous series on show is “Black and Gray” (1969), in which Rothko eschewed frames in favor of edge-to-edge expanses of pigment. The variations he managed to wrest from black and gray are indeed amazing, calling to mind the work of Pierre Soulages. This series has been interpreted as symptomatic of Rothko’s depression in the year before he killed himself, but the view taken here is that they are simply an extension of Rothko’s constant probing of the powers of painting. To support this assertion, the exhibition ends with three brightly colored paintings made only a couple of years before his death.

Rothko summed up his own painting beautifully in The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of Art (unpublished during his lifetime): “The artist invites the spectator to take a journey within the realm of the canvas. The spectator must move with the artist’s shapes in and out, under and above, diagonally and horizontally; he must curve around spheres, pass through tunnels, glide down inclines, at times perform an aerial feat of flying from point to point, attracted by some irresistible magnet across space, entering into mysterious recesses…. Without taking the journey, the spectator has really missed the essential experience of the picture.”

Do take the journey to the Bois de Boulogne to voyage through Rothko’s paintings.

See our list of Current & Upcoming Exhibitions to find out what else is happening in the Paris art world.

Favorite

Very insightful review. I can relate to your experience in absorbing a Rothko abstract. Will certainly make the time to see this exhibit with so many powerful pieces all in one place!