“Étranger Résident: La Collection Marin Karmitz,” an exhibition of the art collection of film producer and distributor Marin Karmitz (the “MK” in the MK2 chain of movie theaters) at the Maison Rouge in Paris feels like a self-portrait of the man himself.

Nearly every one of the some 350 works in the show features people in varying situations – rarely joyous ones – and are in black and white, lending an unusual coherence to the collection, which includes a preponderance of photo series, from Lewis Hine’s street portraits of workers and urban down-and-outs in the early 20th century to faces distorted by masks or veils by Chris Marker, “Crush-art #01 – #15” (2003-08).

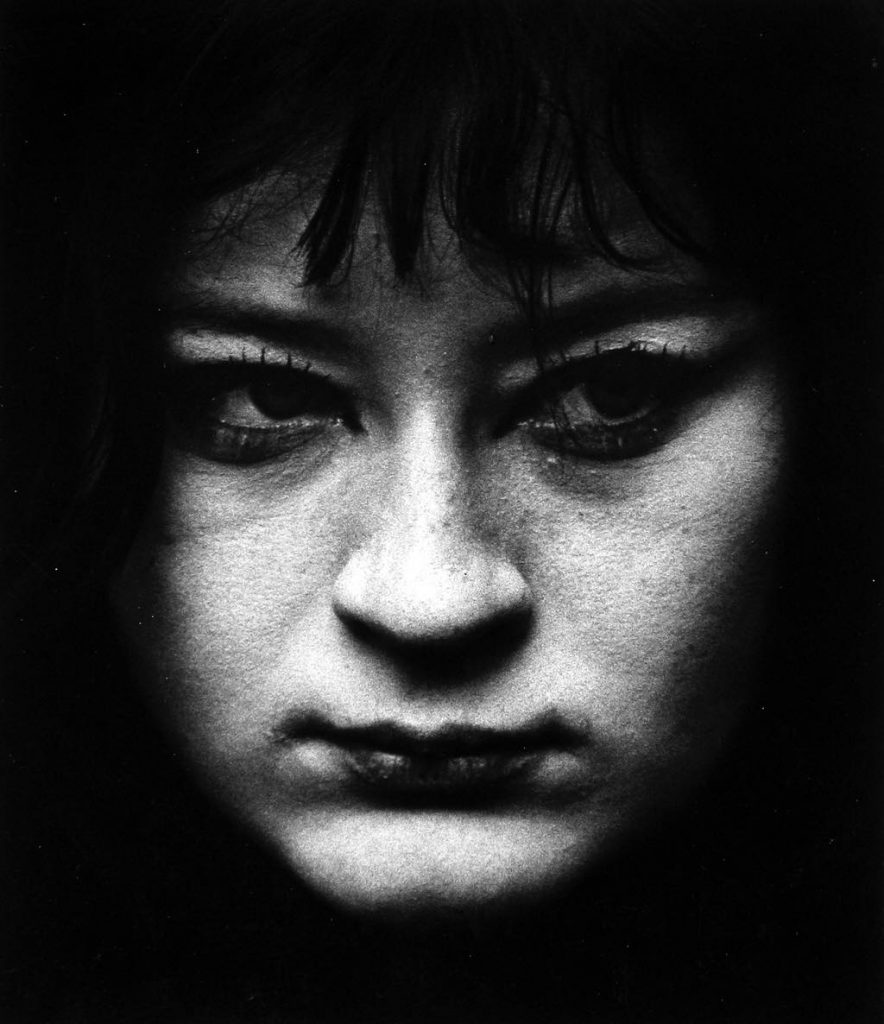

Another feature shared by the photographs in the show is their strong graphic power. I was surprised and pleased to discover a number of fine photographers whose work I was not familiar with, notably the Germans Gotthard Shuh and Dieter Appelt; the Swedish photographers Christer Strömholm (who spent 10 years photographing transsexual prostitutes in Paris in the 1960s, long before Nan Goldin took up the same subject) and Anders Petersen (who also had a penchant for picturing the underbelly of urban life); and the Americans Roy DeCarava, Dave Heath, James Karales and Leon Levinstein (striking tight close-ups from unusual angles on people in the streets of New York).

Others whose work was better known to me and that I was happy to meet again were André Kertesz, W. Eugene Smith, Gordon Parks and Man Ray.

The extensive photographic section of the show is interspersed with some of the most exquisite examples of tribal art I have ever seen, among them a Jalico terracotta statue of a standing woman dating from between 100 and 250 B.C.E.; a thoroughly abstract and highly phallic Mezcala figure from Guerrero, Mexico (c. 300 B.C.E.); and another abstracted human form, an Okvik figure from Alaska (200-100 B.C.E.).

One small room is devoted exclusively to paintings and sculptures by Jean Dubuffet, and the show ends with installations by Annette Messager, Christian Boltanski and Abbas Kiarostami.

Altogether, the exhibition creates an indirect portrait of the collector as an outsider, a “resident alien,” as the title has it. There is a certain overall darkness and sadness there, but also a deep curiosity about and empathy for his fellow humans, especially those who suffer from poverty, oppression or abandonment. One wonders, for example, if Roman Vishniac’s photos of Jewish life in Eastern Europe reminded Karmitz of his own childhood in Romania, from which his Jewish family emigrated to France in 1947, when he was nine years old. I was unable to find out much about this period of his life, however, or how his family experienced the war years.

We get a hint from what he said recently to a French interviewer:, “What touches me in a photo is linked to my own history, the history of a part of the 20th century.”

Before he became a producer working with some of the greatest auteur directors over the past decades, Karmitz was a director himself, but he hasn’t been able to make a film since his 1972 Coup pour Coup, about a group of striking women in a factory, supposedly because of the “revolutionary” politics expressed in his films.

In a way, the show is a return to directing for him: “When putting together this exhibition,” he says, he tried to “tell a story, write a screenplay with all those faces, imagining them as silent actors.”

Don’t miss this wonderful “silent” production at the Maison Rouge.

Note: Sadly, since the Maison Rouge will be closing next year, this exhibition provides one of the last chances to visit.

Favorite

PLease tell us why this special museum is closing. I visit it nearly every time I’m in Paris, and this year also ate lunch there.

The Maison Rouge is privately owned by the foundation of collector Antoine de Galbert, who has decided to close it at the end of 2018, although his foundation will continue. You can read his statement (in English) on the subject here: http://lamaisonrouge.org/en/news-detail/news/fermeture-de-la-maison-rouge-fin-2018/