The artist Sophie Calle is a storyteller whose tales are told in photographs and texts that dredge her memory and transform her personal experiences into something universal we can all relate to, whether they deal with love, heartbreak, death or the lives of strangers. With her new exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, “Sophie Calle: Les Fantômes d’Orsay” (“The Ghosts of Orsay”), however, we see another manifestation of her bottomless curiosity.

The story goes like this: one day in 1978, Calle discovered an unlocked door that led to the abandoned Grand Hôtel d’Orsay in the Gare d’Orsay, the defunct train station and future Musée d’Orsay. Over the next two years, she haunted its guest rooms and public spaces, taking photographs, collecting objects and just hanging out in this strange, deserted world.

Amazingly, for over 40 years, she kept the objects she took home from the hotel – rusty room keys, red-and-white enameled number plaques from the doors, utensils, a “microtelephone” and much, much more, even though she had no plan for them. As the exhibition’s curator put it, “This was Sophie Calle before she was Sophie Calle.”

Today, the fully formed Sophie Calle has finally found a use for those seemingly worthless less souvenirs of the hotel. To make sense of them, she brought on board a real archaeologist, Prof. Jean-Paul Demoule, to help organize these 20th-century artifacts. To create the proper ambiance, the exhibition rooms are decorated with a replica of the hotel’s floral wallpaper, a relic of another era.

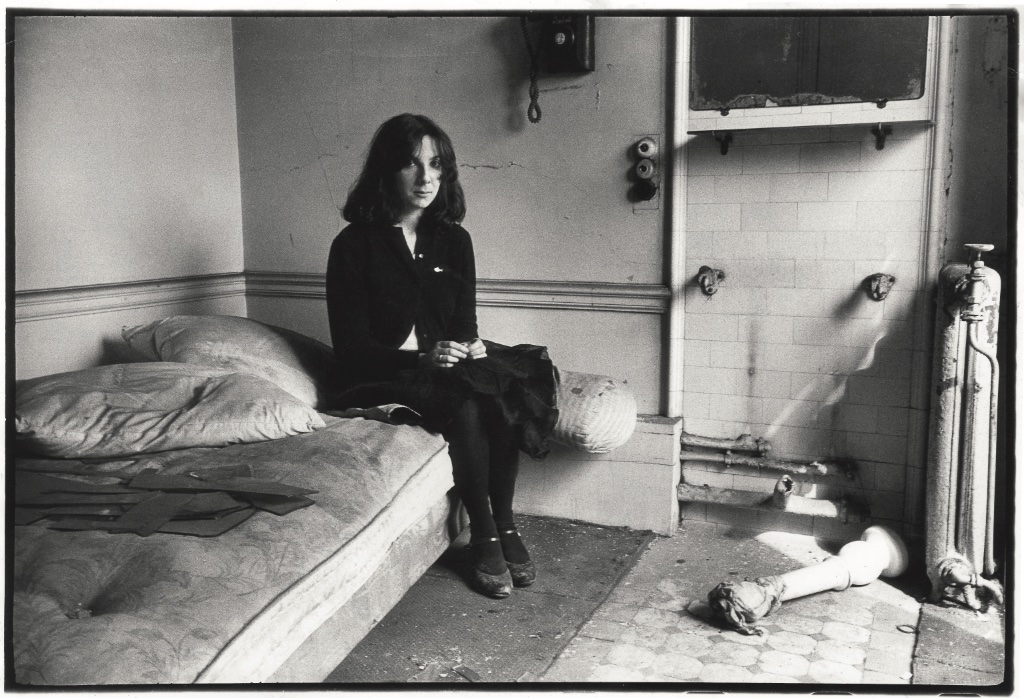

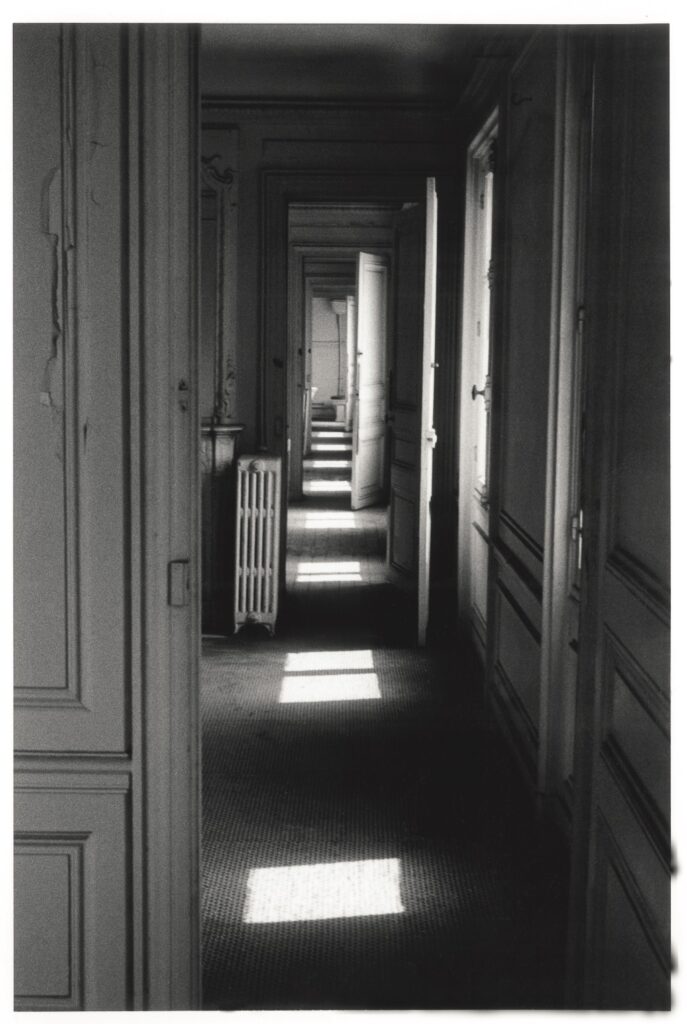

Many of the black-and-white photos she took in the hotel beautifully capture the light from the curtainless windows, as in a shot of a corridor, and another of a series of rooms with open doors between them. The broken furniture, peeling paint, disconnected water pipes, bare mattresses and rubble in the rooms evoke a sense of tragedy, as do the images of a dead cat shown in two different stages of desiccation.

Calle has an uncanny sense for the poignant. Among the most moving of the objects from the hotel are the registration forms of guests. In their own handwriting, we learn a few facts about dozens of probably long-gone guests of the hotel, who were asked to give their name, birthdate, birthplace, nationality, profession and home address. That’s quite a lot of information, amounting to mini-biographies of these “ghosts” of the hotel. A certain Robert Davidson, for example, born in Cupar, Fife, Scotland, on April 13, 1907, lists his profession as “colonial civil servant.” He stayed at the hotel from March 2 to 8, 1940. One wonders what colony he represented and what he was doing in Paris during Britain and France’s “Phoney War” against Germany, a few months before the Nazis invaded France.

Calle has an uncanny sense for the poignant. Among the most moving of the objects from the hotel are the registration forms of guests. In their own handwriting, we learn a few facts about dozens of probably long-gone guests of the hotel, who were asked to give their name, birthdate, birthplace, nationality, profession and home address. That’s quite a lot of information, amounting to mini-biographies of these “ghosts” of the hotel. A certain Robert Davidson, for example, born in Cupar, Fife, Scotland, on April 13, 1907, lists his profession as “colonial civil servant.” He stayed at the hotel from March 2 to 8, 1940. One wonders what colony he represented and what he was doing in Paris during Britain and France’s “Phoney War” against Germany, a few months before the Nazis invaded France.

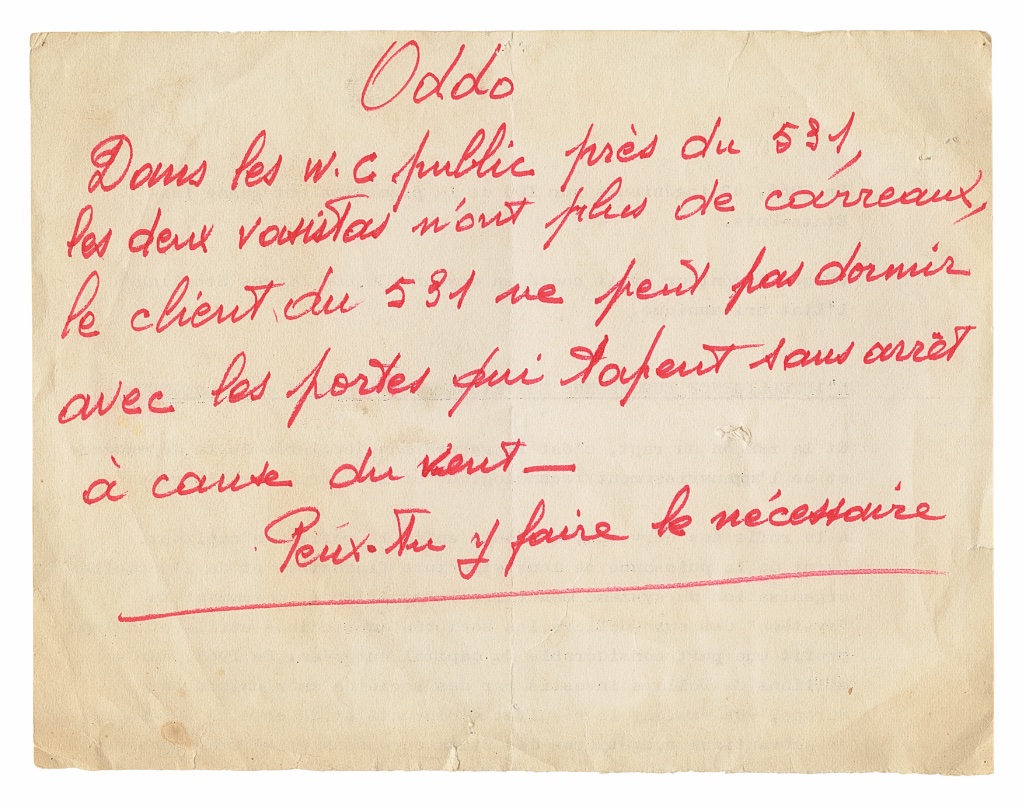

Calle even saved the scraps of paper, normally destined for the trash bin, on which notes to the hotel’s handyman, Oddo (or Odo) were written. These slips of paper really bring the hotel back to life: “Oddo, you left your tools in room 356,” “Oddo, I want to see you at 8 AM about water leaks on the sixth floor.” “Oddo, I unclogged the urinal and the sink.” “Oddo, in the public toilets near 531, the 2 skylights are missing their glass, the guest in 531 can’t sleep with the doors banging all the time in the wind.” And so on. Oddo was a busy man, and he also provided the key to Calle’s fascination with the hotel.

After two years of visiting the hotel, where workmen had started renovations on the first floor and moved up floor by floor, they finally reached the fifth floor, and Calle realized it was time to say goodbye to her refuge. She invited some friends over to party there as a last farewell.

Forty-something years later, when she returned to what is now a museum in preparation for this exhibition, Calle came across a monumental painting, dating from 1904, called “Grand Hiver,” by Cuno Amiet, depicting a tiny skier in a vast sea of snow on a mountainside. One of the museum’s curators told her that originally there had been two other skiers in the image, which the artist had painted out. When the painting is turned over, however, the faint figures of the two missing skiers buried under the paint are visible. For Calle, the existence of these two ghosts “au dos” (on the back) of the painting was a sign, a link to another ghost, Mr. Oddo, bringing her full circle.

Favorite

C’est manifique, mais ce n’est pas la gare

C’est l’hôtel qui était dans la gare.

It would be wonderful if this exhibit became permanent, what a wonderful glimpse into the past. One of my favorite museums.