There is nothing whatsoever “ironique” about what happened in Paris on November 13. Or in Beirut on November 12, or Ankara on October 10, to pick just those examples. I certainly have no intention of making light of the attacks themselves. My first thoughts, like those of every thinking person, are of sympathy for the victims and their families, and sorrow at the specter of so many lives heartlessly cut short in the name of a twisted ideology.

Note: readers who feel that they might be offended by any attempt at humor about any aspect of these events should stop reading here.

In the days that followed, I expected that the general public response, even in today’s online world, would continue to be a show of condolence and solidarity. But I was forgetting Isaac Newton’s first two laws of cyberdynamics:

1) A body of comments in emotional territory tends to stay emotional (the principle of Internetertia).

And:

2) For every action, there’s a vastly unequal and virulently opposite reaction on Facebook.

Some years ago, I had a rather absurd conversation at a dinner party with a young woman who was a self-proclaimed expert on personal hygiene. At one point, she started asking me questions about how I brushed my teeth. (Trust me, this ties in eventually.)

The Q&A, all of which really happened as described, went like this:

“Do you brush right after every meal?”

“Yes.”

“You shouldn’t — you should wait at least an hour after eating. Do you wet your toothbrush after you put on the toothpaste?”

“Yes.”

“That’s bad — toothpaste works better when it’s dry. Do you floss your teeth after brushing?”

“Yes.”

“It’s more effective to floss before. Do you rinse your mouth with cold water?”

“Yes.”

“You should use hot.”

It went on like that for a few more rounds. I got the impression that she was just arbitrarily declaring whatever I did to be wrong.

This is the experience that many (and probably most) Paris sympathizers have had on the Web over the past 12 days. Any well-intentioned gesture would immediately be branded by someone as wrong for some reason.

The first wave of criticism was the predictable one-death-up-manship that always follows major outbursts of violence. It can be summarized as, “My preferred atrocity outweighs your atrocity because the body count is higher.”

In compliance with Newton’s third law, this comment must be accompanied by the words, “And no one’s talking about it!” Which in turn should be, but never are, accompanied by the words, “Except me and the 10 million other people saying, ‘And no one’s talking about it!’”

A day or so later, the slogan “Pray for Paris” was denounced as being too religious for a secular state like France, and Facebook’s blue-white-and-red flag overlay for users’ profile pictures was deemed too jingoistic for French sensibilities.

Both of these points have merit, by the way, and many people expressed them in a measured, rational tone. But, of course, in keeping with Internet tradition, there were even more people who carefully considered the facts, weighed both sides of the issue, and decided to get all huffy about it.

Even though the Eiffel Tower is now lit up in the national colors every night to commemorate the terror strikes, the Facebook flag filter triggered an argument that has not died down yet, and even shows signs of escalating into armed sectarian conflict.

The free and open exchange of ideas has evolved through several stages:

• People who put the French flag filter on their profile picture are jerks.

• People who say that “people who put the French flag filter on their profile picture are jerks” are jerks.

• People who say that “people who say that ‘people who put the French flag filter on their profile picture are jerks’ are jerks” are jerks.

And so on. As of this writing we’re up to about a dozen layers of nested quotations ending with “are jerks.” I’m sure that pointing this out makes me a jerk.

But it’s all just human nature. Crisis situations bring out both the best and the worst in any population.

As an example of the former, on the night of the attacks hundreds of Parisians took to the social networks to offer free lodging to residents who couldn’t go home because their streets were blocked off with crime scene tape.

Here’s a typical Tweet from that night:

Willing, TBH eager, 2 offer bed, or rath. 1/2 of bed, 4 stranded Parisian SWF, likes music, dinners out & long walks around police cordons.

The worst emerged over the next few days in the form of false bomb alerts and the actions of an exceedingly clever, witty practical joker who was one of the very few intellectuals smart enough to perceive the humor in setting off firecrackers in the crowd of mourners at Place de la République, sparking a stampede.

Even lower on the scum scale is the blogger who sagaciously announced that the Paris attacks never took place. According to him they were a hoax, faked by the authorities for some unexplained but no doubt devious, conniving purpose.

I’d rather gargle with Seine water than dignify this pathetic delusion with a link to confirm its existence, but the “proof” was that one of the videos of survivors fleeing the concert hall emergency exit showed a few passersby across the street who “look so calm they must be actors.”

It occurs to me that it would be just as plausible to say, “The passersby look so agitated they must be actors.” Or even, “The passersby strike such a perfect balance between calm and agitated they must be actors.” That’s the great thing about conspiracy evidence: seek and you shall find.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. This is the kind of “evil plot” theory that pops up in the wake of virtually every tragedy, essentially because it allows the theorists to flatter themselves with the attractive, narcissistic stance of “I’m right and everyone else is wrong, because my cherry-picked information allows me, from thousands of miles away, to know what really happened.”

In this case, if the “whistle-blower” is right, the news will come as a tremendous relief to the 130 or so families whose loved ones, for no imaginable reason, with no planning and simultaneously from the same handful of places, all suddenly decided to run away forever, first taking care to leave behind clones of themselves that had somehow been shot to pieces.

Back in the realm of brain functions, many people, reflecting on the horror of that night, have been asking: in the aftermath of the shootings, will the French lifestyle be changed forever?

I am convinced that the answer is no. It survived the siege of 1870, that unpleasant little episode called World War I and then the sequel. I personally don’t think that the war on terror is going to dampen the nation’s spirit significantly.

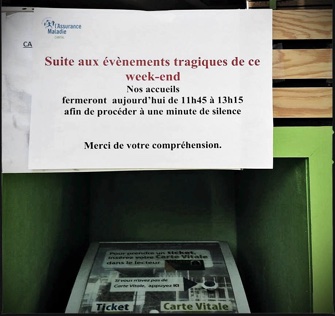

Those who are concerned about the future of France’s art de vivre can take heart in a note that appeared on the door of the national health insurance office in the town of Cantal on November 16th:

It says, “Following the tragic events of last weekend, our offices will close today from 11:45 to 1:15 in order to observe a minute of silence.” Vive la France — et le lunch break!

Last-minute flash! Important travel advisory!

A special note to Americans who have a vacation coming up and wonder if they’ll be safe in a place where any second they might be brutally slaughtered by a crazed rampaging sociopath with easy access to an arsenal of assault weapons:

Yes, you really should get out of the United States for a while. I recommend a trip to France, where your chances of being murdered with a firearm are 1/50th what they are at home.

© 2015 Paris Update

FavoriteAn album of David Jaggard’s comic compositions is now available for streaming on Spotify and Apple Music, for purchase (whole or track by track) on iTunes and Amazon, and on every other music downloading service in the known universe, under the title “Totally Unrelated.”

Note to readers: David Jaggard’s e-book Quorum of One: Satire 1998-2011 is available from Amazon as well as iTunes, iBookstore, Nook, Reader Store, Kobo, Copia and many other distributors.