Back at the beginning of Japan’s Tokugawa shogunate, its founder, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), had five roads built to connect the capital of Edo (now Tokyo) to the rest of the country. A couple of centuries later, two ukiyo-e (“images of the floating world”) artists, the brilliant Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Keisai Eisen (1790–1848), made a series of these woodblock prints illustrating each one of the 69 staging posts on one of the roads, the Kisokaidō, which was traveled on foot by pilgrims, monks, merchants and tourists (nobles, however, were carried on sedan chairs or horses). This series and another, very different one on the same topic by Utagawa Kuniyoshi are the subject of a marvelous exhibition at the Musée Cernuschi: “Voyage sur la Route du Kisokaidō. De Hiroshige à Kuniyoshi” (“Journey on the Kisokaidō Road: From Hiroshige to Kuniyoshi”).

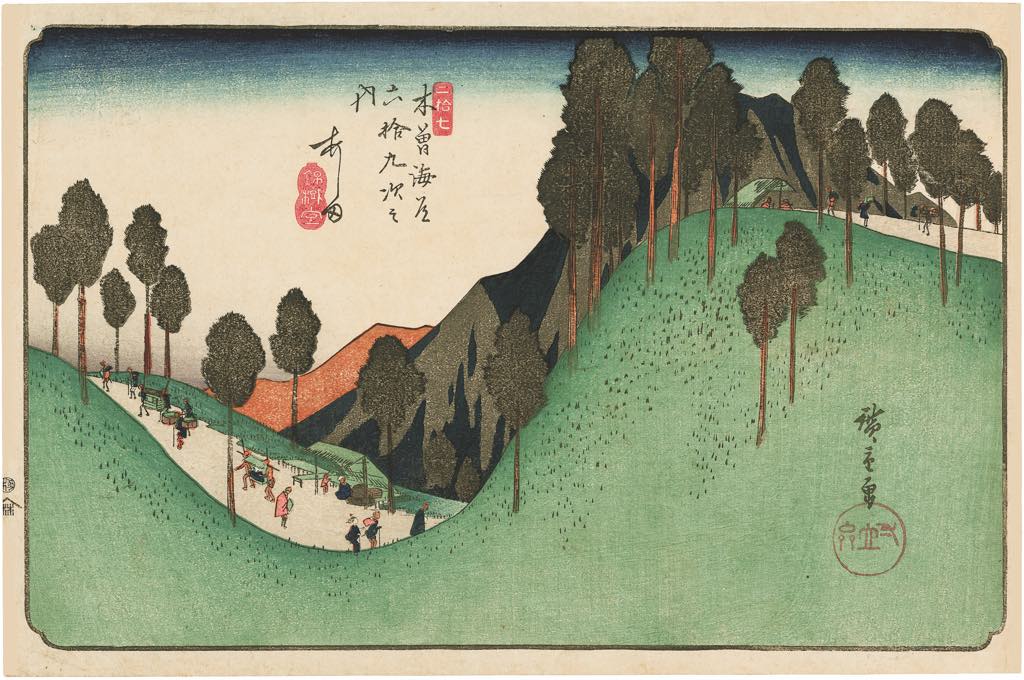

For unknown reasons, 24 of the drawings in the series were done by Eisen, who disdained topographical accuracy in depicting the staging posts, and 47 by Hiroshige, who had actually traveled the road.

While Eisen’s contributions are charming and often beautiful, focusing more on people, Hiroshige’s really pop out with their rich colors (especially the blues), sensitivity to nature and unusual points of view. One example of the latter is “27. Ashida,” in which the travelers are seen from a distance, with green mountains looming up in front of them. Hiroshige also excelled at capturing the atmosphere along the road, as in “40. Suhara,” in which porters run toward a shelter under which a monk is smoking a pipe and a pilgrim is praying. As the curators note, this image “perfectly captures the experience of the traveler – we can feel the warm summer rain and the suffocating humidity.”

Many of the prints tell a story, which we are not always able to decipher without help from the curators, who have provided explanations for some. One of Eisen’s, “23. Iwamurata,” depicts a brawl between a group of blind pilgrims, observed by a barking dog, while another, “10. Fukaya,” shows a group of geishas and female servants in front of an inn, with dark silhouettes of men lurking behind them in the shadows. The prints mentioned here and the rest of the series can be seen on this site.

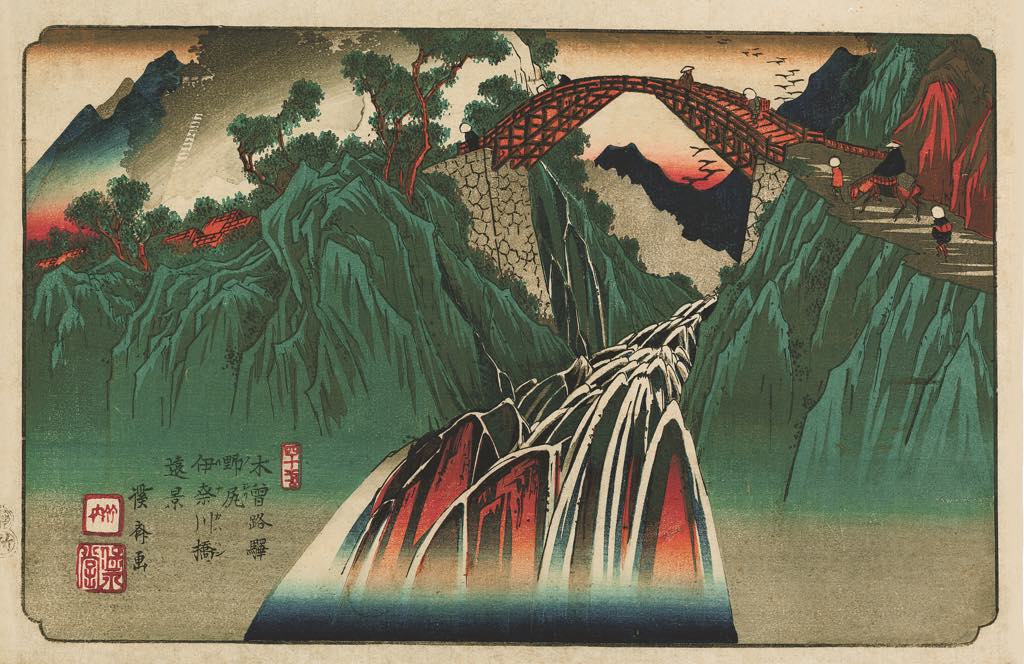

The second series on show, The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō Road by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), is another story and another style entirely. The main subject matter of each action-packed print is a literary or historical event, often connected to the staging post (depicted only in a small vignette) by a play on words. One example is the gruesome “Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu.”: Kuniyoshi puns on the staging post’s name, “Oiwake,” by associating it with Oiwa, the heroine of a famous Kabuki play, who is poisoned by her philandering husband and kills herself with his dagger when she sees in a mirror her disfigured face and hair falling out (“Oiwa” + “ke” (hair) = “Oiwake”).

We Westerners are lost in the face of this complexity and the unfamiliar cultural references, but luckily some explanations are provided here as well. For many of these mysterious (to us) prints, I wished I could know more about what was going on; in “7. Okegawa,” for example, a man is trapped inside a wooden barrel being given a drink by a girl, and in another, a woman is beating up a monstrous man. The Kuniyoshi Project site provides (not always satisfying) captions for each of the prints.

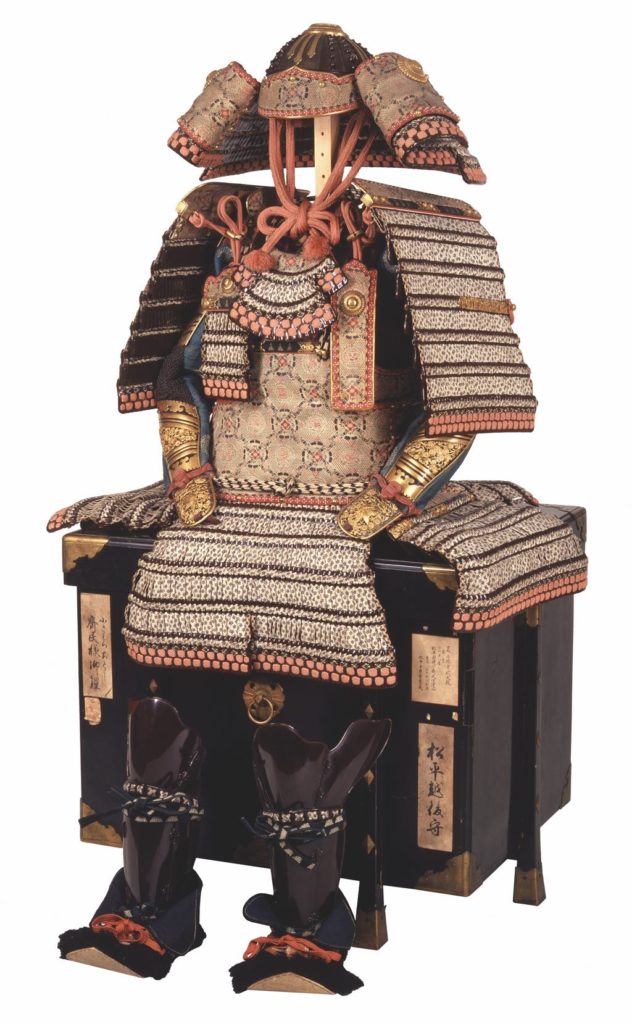

The exhibition is accompanied by a few gorgeous, elaborate and beautifully crafted antique objects that relate to the images, including picnic sets, smoking kits and an incredible suit of armor.

You could spend hours being drawn into the colorful and complex worlds depicted in these wonderful prints. Don’t miss this exhibition if you want a total break from our current reality.

Favorite