I have said it before and will probably say it again: the Musée Zadkine is one of my favorite museums in Paris, with its small light-filled house and studio set in a garden, the whole charming ensemble cut off from the noise of the city – the only sounds to be heard come from the squeaky wooden floor inside and the birdsong outside.

The city-owned museum frequently holds interesting exhibitions that shed new light on the work of Russian-born French sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1888-1967), who lived and worked there between 1928 and ’67.

The current show, “L’Âme Primitive” (“The Primitive Soul”), uses the judgment-laden word “primitive” in reference to “primitivism,” the turn-of-the-century movement of artists who rejected academism and the classic heritage of the Renaissance and looked to non-Western and archaic sources in their search for “authenticity.” Zadkine, who joined the Cubist movement after he arrived in Paris in 1910, was – like many of the artists of his time – greatly influenced by African and Greek art. The show compares Zadkine’s work with that of a number of other modern and contemporary artists of all stripes to examine how this desire for a new way of depicting the world was – and is – manifested by them.

The correspondences between works are, of course, evocative rather than direct, and speak of the various artists’ desire to go beyond appearances and seek the “soul” in their subjects. In the first section, “Reverse Perspective,” classical forms are ignored or distorted. A couple of works by Valérie Blass (b. 1967), for example (one of which is seen in the photo at the top of this page), rip apart the human body and force it into “unnatural” geometric positions or flatten it and hang it in space. Nearby, Zadkine’s beautiful marble sculpture “Maternité” (1919) compacts the bodies of mother and child into a series of interlocking triangles.

You could easily miss “Limbé” (2020), a film by Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc (b. 1977) being shown on the wall directly above “Maternité,” since all you can see at first is a tiny, upside-down face. The body of dancer and choregrapher Betty Tchomanga gradually comes into view as she performs a fascinating contortionist dance from Trinidad associated with voodoo and death.

The human body is subjected to many transfigurations by these artists, among them Abraham Poincheval (b. 1972), who likes to combine “noble” materials with “poor” ones. Here we have two “Lion Men,” one subtly drawn on gold and silver leaf pasted onto cardboard and another roughly sculpted in bronze.

Auguste Rodin’s impressionistic drawings of dancers and small clay sculptures of dancer and acrobat Alda Morena in movement fit wonderfully into this section. The confrontation with Miriam Cahn’s 2012 painting “Kriegerin” (“Warrior”), makes perfect sense here, but still comes as a shock with its lurid colors, uncompromising nudity and ferocious stance. The strange, pugnacious, highly sexualized work of the feminist Swiss painter Cahn (b. 1949) suddenly seems to be everywhere these days and is indeed hard to ignore.

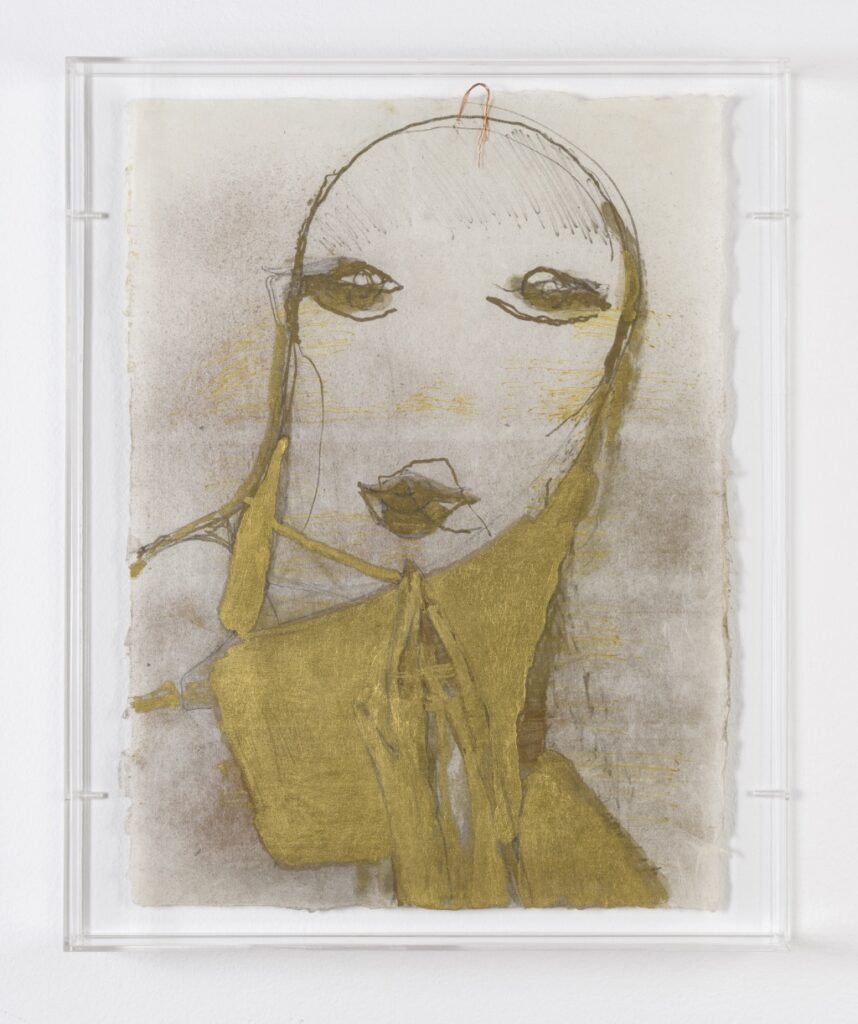

Like Cahn, Arte Povera artist Marisa Merz (1926-2019), who is represented by a few pieces in this show, reduced the human face to its most basic elements, sometimes almost completely wiping away the features.

Many of the works in this exhibition elicit an eerie, sometimes downright disturbing reaction, all the better to encourage us to open our eyes and look harder – into the soul, perhaps?

Favorite