Painting Through the

Eyes of Others

“Femmes à cheval à Robinson” (1887). © D.R.

Emile Bernard (1868-1941) is a painter whose work I have occasionally had an intriguing glimpse of in various group exhibitions, but retrospectives of his work seem to be rare. After seeing the one now on at the Musée de l’Orangerie, the first to be held in France, I can see why. He is an artist who is difficult to pin down, who never settled on a single style. This seems perfectly normal when he was a young man finding his way, but Bernard never stopped absorbing influences, experimenting and taking on new styles, always accompanying his efforts with theoretical explications, for he was also a writer and poet.

The exhibition starts with the Lautrecian “L’Heure de la Viande” (1885-86), the “viande” being the women negotiating with men in a bar. The colors soon brighten and gradations disappear as styles are embraced and then rejected one after another – Impressionism, Cloisonnism (flat planes of color outlined in black, inspired by Japanese prints), Synthetism (a “synthesis” of an object’s appearance, the artist’s feelings about them, and line, color and form) and Symbolism. Once he embraced the latter movement, he insisted that spirituality and imagination took precedence over the representation of reality.

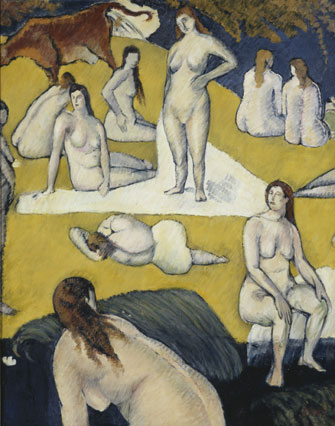

As you look at these paintings in all their

“Les Baigneuses à la Vache Rouge” (1889). © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski

variety of styles, the names of one artist after another will pop into your head: Lautrec, Gauguin, Manet, Puvis de Chavannes, Maurice Denis and above all Cézanne.

Bernard claimed that Gauguin took inspiration from him rather than the other way around, but, while this may be true, a comparison of similar paintings by the two artists – Gauguin’s “La Vision du Sermon” (1888) and Bernard’s “Les Bretonnes dans la Prairie” (1888) on one of the wall panels shows that Gauguin’s version outdoes Bernard’s in verve and imagination. The two painters, who had met in Pont Aven, soon fell out after a dispute about who had founded Cloisonnism.

In 1893, when Bernard was still in his 20s, he traveled in the Middle East, eventually settling down in Egypt for a time. There he completely reversed himself, returning to the realism he had rejected while living in France as he searched for a style “that would be both modern and outside of reality,” and in which style reigned over the object. His encounter with the “human beauty” of the Middle East drew him back toward naturalism.

Later travels in Italy and Spain and his discovery of the Old Masters, especially the great Venetian Renaissance painters, confirmed him in his decision return to realism and tradition.

In the last few rooms of the show, it’s hard to believe that the paintings are by the same artist as those in the first parts of the exhibition. Bernard seems to be painting through the eyes of other artists, landscapes through the eyes of Cézanne, for example, or mythological scenes like “Hercules versus the Amazons” (1927) through the eyes of classical painters.

This “return to order,” a reversal that many initiators of modernity made as they grew older, did not serve his reputation and seems to have harmed his legacy. He didn’t see it that way, however; he thought he was doing nothing less than “saving art itself,” a mission he found more important than his own art, “a great battle” that he had to undertake alone by pointing out the “lies, errors and impotence” that he saw in art exhibitions.

Bernard was undoubtedly a talented painter – I liked many of his early works and some of the later ones, especially the portraits (notably that of his grandmother, a redoubtable old woman in black, and that of Mademoiselle Coste, a barefoot older woman half reclining on a sofa) – and as a writer left behind valuable accounts of his friendships and encounters with some of the great artists of his day, including Gauguin, Cézanne and Van Gogh. Sadly, apart from some of the more interesting paintings from his youth, that seems to be his greatest contribution to the development of modern art, rather than his paintings themselves.

Musée de l’Orangerie: Jardin des Tuileries, 75001 Paris. Métro: Concorde. Tel.: 01 44 50 43 00. Open Wednesday-Monday, 9am-6pm. Admission: €9. Through January 15, 2015. www.musee-orangerie.fr

Click here to read all of this week’s new articles on the Paris Update home page.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

Support Paris Update by ordering books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

© 2014 Paris Update

Favorite