In our world of conflict, plague, dictatorships and the rise of the far right, it is hard to escape the feeling that things are regressing rather than progressing. However, one discernible area of positive advancement can be found in the French art world.

If an exhibition like the current “Romantic Heroines” at the Musée de la Vie Romantique had been staged only a decade ago, the eroticization of dying heroines depicted in the nude or with breasts spilling out of diaphanous figure-hugging dresses would have been presented simply as “erotic” and entirely unproblematic. But here, the joint curators of the exhibition, Gaëlle Rio and Élodie Kuhn, not only question the way these heroines are objectified by the male gaze but also present many more works by female artists than previously would have been the case.

“Romantic Heroines” opens with a room devoted to mythological and historical heroines as represented by 19th-century artists. The ancient Greek poet Sappho, now best known for the poetry she wrote celebrating lesbian love, was a particularly popular subject for Romantic artists, who usually managed to recast her as a heterosexual woman, killing herself over her love for a male boatman, Phaon. The painting “Sapho à Leucate,” by Antoine-Jean Gros, first exhibited at the 1801 Salon in Paris, is particularly striking. Sappho, posed in a nocturnal seascape, is shown clutching the poet’s lyre on the edge of a precipice. Even though she is about to plunge to her death, she seems instead to be launching herself upward in the direction of the moon.

The deaths of other mythological/historical figures shown in the exhibition include those of Antigone, whose demise is depicted in dramatic style by the little-known artist Victorine Genève-Rumilly (1789-1849), displaying her neoclassical training in the choice of poses; Cleopatra, who is given the full-nude treatment by Jean Gigoux (1806-94), with a barely discernible asp on her wrist; and Mary Queen of Scots, whose execution attracted the particular attention of French artists. Among the several representations of Mary in paintings and books in the exhibition, I found the photographic depiction of her clutching prayer beads (emphasizing her Catholicism) by the Victorian British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-79) particularly intriguing. Other historical figures appearing in this part of the exhibition are Queen Christina of Sweden, Héloïse (lover of Abelard), and, not surprisingly, Joan of Arc.

Another subject of fascination in the 19th century was the supposedly unnatural woman murderer, such as the mythological figure Medea (look out for the Delacroix oil study for “Médée Furieuse”); the real-life Beatrice Cenci, who killed her abusive father in the 16th century (shown in another photographic staging by Cameron); and Charlotte Corday, who assassinated Jean-Paul Marat at the time of the French Revolution.

The second part of the exhibition is devoted to heroines from fiction. Shakespearean figures were particularly fascinating to Romantic artists – the Bard’s plays enjoyed particular success in France in the 1820s – and the show includes a number of pieces portraying Desdemona (by painters like Delacroix, Jules Robert Auguste and Théodore Chassériau), Lady Macbeth (Charles-Louis Müller), Juliet (Delacroix), and Ophelia (Léopold Burthe). As good as these works are, it is regrettable that not a single example of the vast corpus of Shakespearean heroines by British Pre-Raphaelite artists was secured for this show.

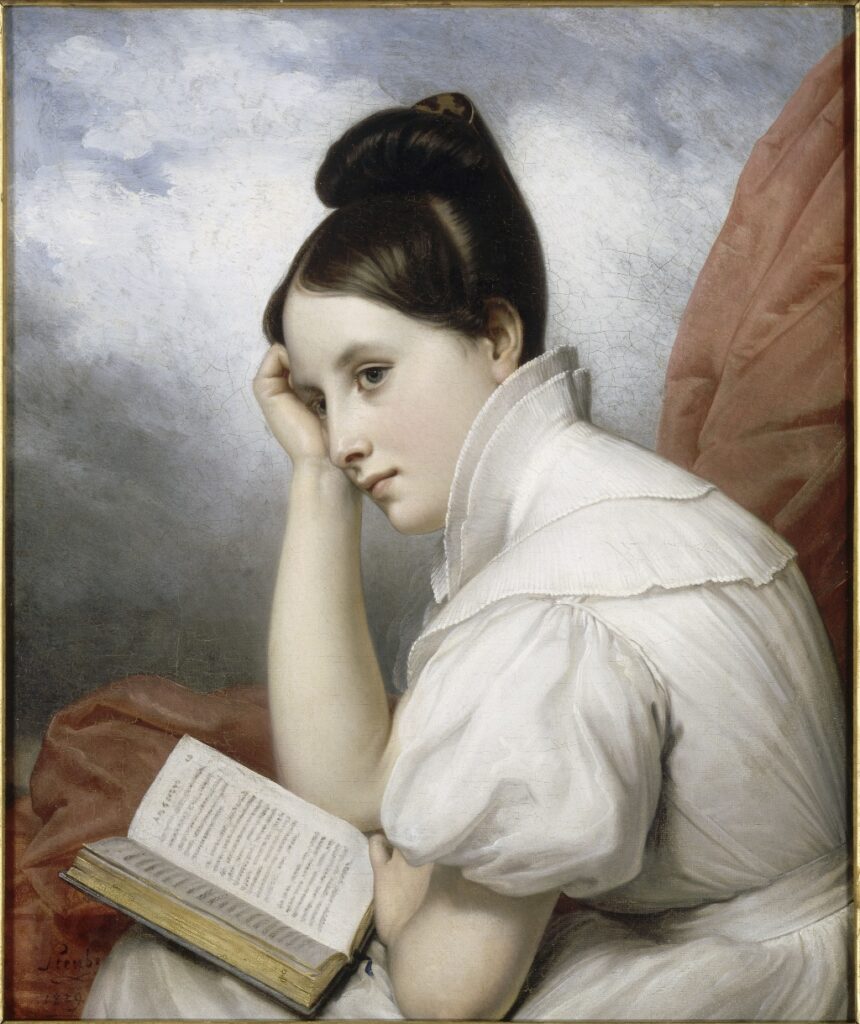

With the rise of the novel in 19th-century France, artists began to represent literary heroines from works by writers like François-René de Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo, Germaine de Staël and – especially appropriate given her strong ties to the house in which the Musée de la Vie Romantique is located – George Sand. In addition to various paintings and lithographs, you can listen to extracts from various novels, including Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, in which Emma Bovary’s identification with the romantic heroines she loved to read about contributed to her downfall. Perhaps my favorite painting in this section of the exhibition is the portrait of a female reader, “La Liseuse,” by Charles de Steuben (1788-1856). With her head leaning on her arm as she gazes into the distance, a novel balanced on her knees, the reader is no doubt dreaming of other worlds as experienced by her literary heroines.

Women who performed as Romantic heroines on the stage and who themselves were often represented in painting, sculpture and ceramics have not been forgotten. We see depictions, for example, of the Comédie-Française great Rachel starring in Jean Racine’s Phèdre; the British Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, who went on to marry the smitten composer Hector Berlioz; dancers like Mare Taglioni; and the singers Giuditta Pasta, Henriette Sontag and Maria Malibran. In this final room, there are also short video clips of more recent dancers and singers interpreting the roles of heroines from the 19th century.

If you are in Paris over the summer, this invigorating exhibition is well worth visiting. Do not forget to have a look at the permanent exhibition in the main house while you are there. And, if you are in need of some light refreshment, the delightful salon de thé in the leafy courtyard is an ideal place to settle down with a 19th-century French novel and immerse yourself in the life of your favorite Romantic heroine.

Favorite

I saw this exhibit back in April and I agree wholeheartedly with your assessment, Nick. It was a definite an eye-opener, gently forcing a re-think of how the portrayal of the female form, especially in its mythological, historic and fictional contexts, shaped western understandings of feminine psychology and desire. Certainly worth seeing.

Thank you for your kind comments, John. Isn’t it great to see previous assumptions being questioned?