The latest exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, always on the lookout for new ways to present its collection of 19th-century art, is “Huysmans Critique d’Art: De Degas à Grünewald, sous le Regard de Francesco Vezzoli.” That long title translates into a show presenting art that was appreciated (or not) by the French art critic and novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907). The exhibition was co-curated by Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli, known for his videos and reinterpretations of the work of other artists (often decorated with embroidery), and some of his works are thrown in for good measure.

Huysmans was a fascinating character. Like Franz Kafka and Henri Rousseau, he supported himself as a bureaucrat – he was a worker bee for the French civil service for over 30 years – while pursuing his creative work on the side.

Originally a staunch supporter of Naturalism in art, his tastes changed over the years. His fame was assured by his Decadent novel À Rebours (Against Nature), published in 1884 and an inspiration for Oscar Wilde, among many others, including the controversial contemporary novelist Michel Houellebecq. Against Nature’s protagonist is the extremely neurotic aesthete Jean des Esseintes, who tries to escape from the despised bourgeois world into the higher realms of art by isolating himself in a country château.

This exhibition will be far more understandable and enjoyable for those who have read Against Nature, but those who don’t have the time or inclination to slog through it can get a good summary from the well-written Wikipedia entry on the book, which sets the stage admirably: “Throughout his intellectual experiments, Des Esseintes recalls various debauched events and love affairs of his past in Paris. He tries his hand at inventing perfumes and creates a garden of poisonous tropical flowers. Illustrating his preference for artifice over nature (a characteristic Decadent theme), Des Esseintes chooses real flowers that apparently imitate artificial ones. In one of the book’s most surrealistic episodes, he has gemstones set in the shell of a tortoise. The extra weight on the creature’s back causes its death.”

That last sentence explains why the exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay includes a sculpture by Vezzoli, “Tortue de Soirée” (Evening Turtle, 2019), of a jewel-encrusted tortoise. The real-life perpetrator of this turtlecide and the owner of the home that inspired the fantasmagorical interiors described in Against Nature was Count Robert de Montesquiou, who served as one of the models for Marcel Proust’s effete character Baron de Charlus, along with Jean Lorrain. The exhibition includes portraits of these two men – both of them dandies who dabbled in Symbolist poetry – the former by Giovanni Goldini (pictured at the top of this page) and the latter by Antonio de La Gandara.

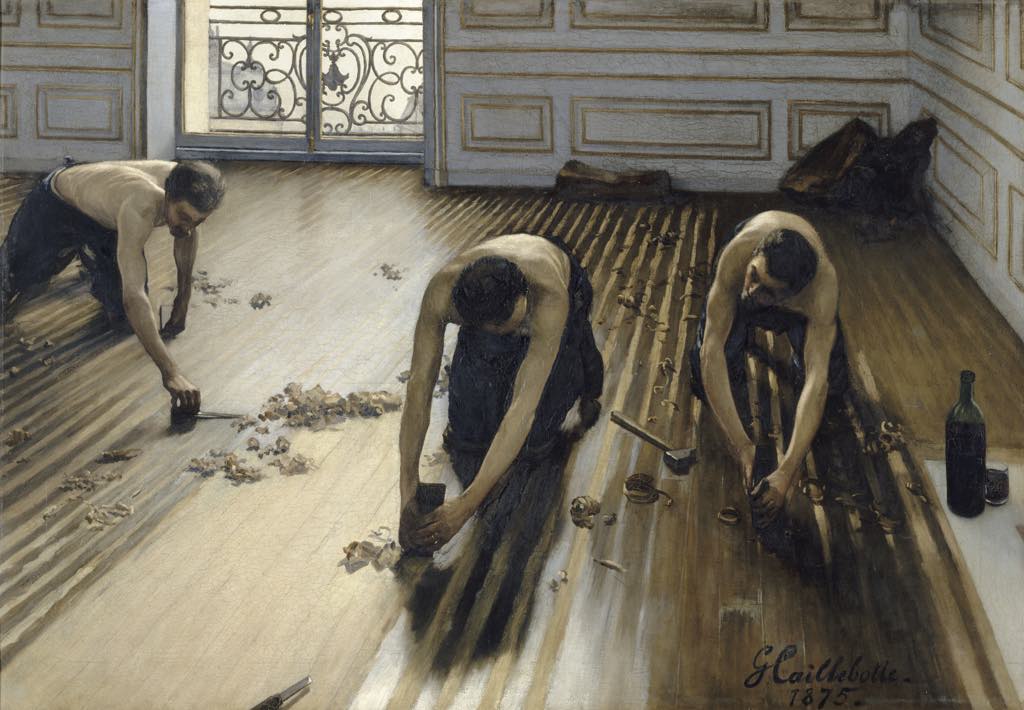

The exhibition begins with works by artists praised or viciously ridiculed in Huysman’s critical writings. He was an early supporter of the Impressionists and especially of Degas, Manet and Caillebotte, and we have here examples of their works, including Degas’ famous “L’Absinthe.”

To give you an example of one of his colorful and amusing attacks on academic painters in his criticism: he speaks of “the gaseous style” of William Bouguereau and describes the goddess in his “The Birth of Venus” as “a badly inflated balloon” that looked as if it belonged on “a sugared-almond box.” Judge for yourself: the painting is on display.

The second room, with wallpaper inspired by the interior of Des Esseintes’ home, is filled with Symbolist works by artists appreciated by Huysmans, among them Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon and Félicien Rops

After having passed through Naturalism and Decadence in his novels and his tastes, Huysmans moved on to another extreme and became a devout Catholic and even an oblate (a lay monk). The show pays tribute to his rediscovered faith with various works with religious themes, including the Ingres pictured above, and ends with Vezzoli’s set of three paintings, “Jesus Christ Superstar” (2019), based on Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16).

This tour of 19th-century art through the eyes of one of its great eccentrics is quite a trip, but to really enjoy it, keep the biography of the man behind it in mind.

Favorite