Having visited the writer Colette’s childhood home in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye on a sun-kissed spring day last year with two good friends, I suppose it was payback time when I arrived alone at the exhibition “Les Mondes de Colette” at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France amid howling autumnal gales and rain. Shredded umbrellas aside, however, this multifaceted, multisensory show is a total delight.

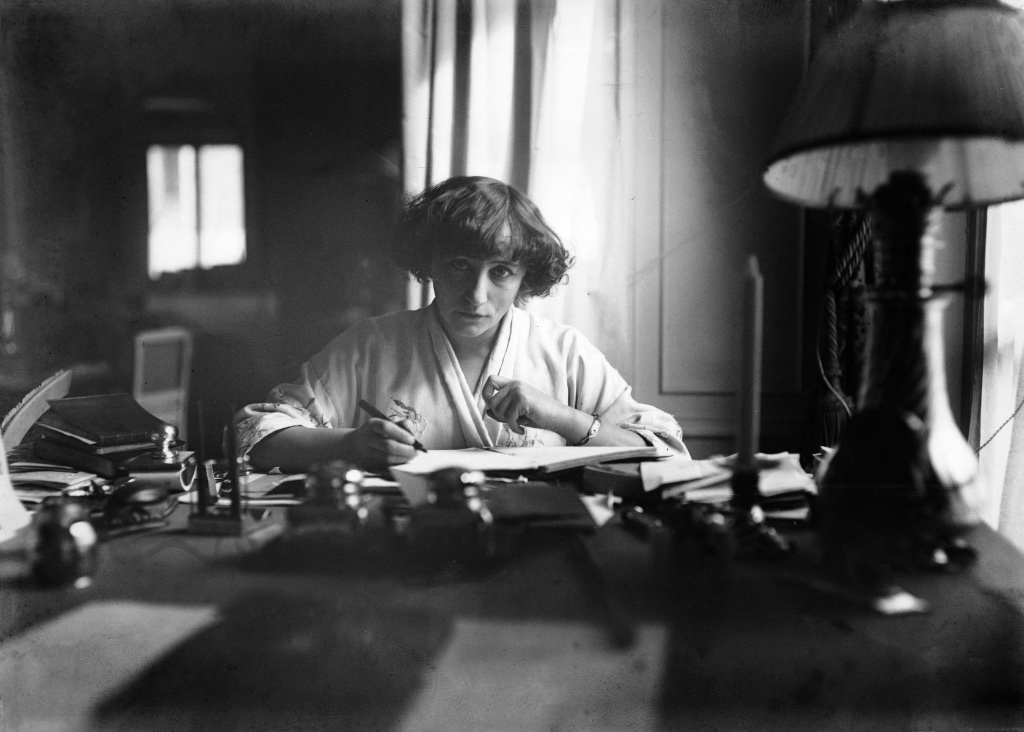

The extraordinary diversity of Colette’s long life (she was born in 1873 and died in 1954) certainly lends itself to a lively, wide-ranging exhibition, but the curators have succeeded in achieving something almost impossible: paying full respect to Colette as a writer (with a wonderful range of displayed manuscripts) while at the same time bringing vividly to life the glories and outrageousness of a person who refused to conform to the norms of her time.

The first part of the show evokes memories of Colette’s childhood. Of her immediate family, her mother – known as Sido in so many of Colette’s writings – looms largest in Colette’s life. (Later in the exhibition, the touching final letter written to her daughter by Sido while she was close to death in 1912 is displayed.) Sido communicated to Colette not only her formidable intellect and independent spirit, but also her love of flora and fauna. Colette’s emotional connection to the garden cultivated by her mother in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye (still there today) can be seen in many of her later writings. It’s an inspirational choice of the curators to include little panels that can be lifted to release the scent of various plants and flowers described by Colette. Another highlight of this section is to listen to and watch extracts from Maurice Ravel’s one-act opera, L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, written between 1919 and 1925, and set to a libretto by Colette. Letters between the composer and writer are also displayed.

The second section (“The World”) covers an extraordinary time in Colette’s life when, separated from her first husband, Willy, she had to make a living and began touring with various dance and music hall troupes as a performer not only in Paris but also across the whole of France (a map shows the many towns and theaters she visited). Perhaps most scandalously for the time, this was when Colette took up with a female lover, Mathilde de Morny, known as Missy. Playing an Egyptologist in a 1907 pantomime entitled Rêve d’Égypte (Egyptian Dream) at the Moulin Rouge, Missy kissed Colette (in the role of a revived Egyptian mummy) on the lips, leading to a near riot and the suspension of performances, with Missy being banned from the stage.

We also learn that Henri Matisse was inspired by Colette in his paintings of dancers from the world of performers she frequented, some of which appear in the exhibition.

This section also covers the lives of kept mistresses and courtesans from the demi-monde represented in Colette’s fiction, notably Chéri (1920) and Gigi (1944). Scenes from film versions by Stephen Frears and Vincente Minnelli of those books are available to watch. Most fascinating, though, are a letter to Colette written by Audrey Hepburn, who played the lead role in the New York stage production of Gigi, and a delightful photo of the elderly writer and the up-and-coming actress together, with Hepburn’s head resting gently against Colette’s shoulder.

Colette constantly reinvented herself over the course of her life, and the same section of the exhibition includes her unexpected foray into the world of beauty salons. Some of the cosmetics ranges that she developed for the Printemps department store are on show here.

The next part of the exhibition, devoted to “Writing One’s Self,” focuses particularly on what would now be termed Colette’s autofiction, drawn very much from her own experiences. Examples here range from the series of “Claudine” novels, which initially appeared under her first husband Willy’s name, to books like Chéri and Le Blé en Herbe (1923) which took their inspiration from the five-year affair she had with Bertrand de Jouvenal, 30 years her junior. As if the age gap were not scandalous enough, her lover was the son of her second husband, Henry de Jouvenel, whom she had married in 1912 after her divorce from Willy. After separating from Henry in 1923, she found time to take up with Maurice Goudeket in 1925, eventually marrying him a decade later.

The show also follows Colette’s prolific journalistic writing (more than 1,200 articles) over the first half of the 20th century, in which she commented on both world wars, wrote about various criminal cases, described her visits as a special envoy to Morocco and New York, and devoted around 30 articles to the nascent art form that was the cinema.

This part of the exhibition ends with a touching extract from a documentary made in 1952 by Yannick Bello in which Colette and her friend and fellow writer Jean Cocteau discuss in an apparently unscripted moment the meaning of laziness and different ways of doing nothing (Cocteau was evidently trying to convince Colette to continue writing).

The final section, “La Chair” (literally, “The Flesh” but cumbersomely and ungrammatically rendered as “The Ways of the Sensuality”), returns to many aspects already covered elsewhere in the show but highlights the role played by desire in Colette’s writings. Even though her ideas on the differences between the sexes are now deemed somewhat conventional – in spite of her own sexual nonconformity – it is perhaps particularly telling that the author most quoted by Simone de Beauvoir in her seminal book, The Second Sex, is Colette, someone who wrote so closely about female desire and autonomy of thought and action.

I urge you to brave all weathers to visit this wonderful tribute to an extraordinary writer and human being.

Favorite