I have often been struck by the luminous beauty of a painting by Impressionist Camille Pissarro (1830-1904) when I come across his work in a group show, but “Pissarro à Éragny: La Nature Retrouvée” at the Musée du Luxembourg is the first monographic exhibition I have seen of his work.

The show concentrates on the paintings and drawings he made from the time he moved to the village of Éragny in Normandy in 1884 until he died. The place was a constant inspiration to him, and he never stopped painting the surrounding countryside in every light and every season.

Although Pissarro was an active, card-carrying Impressionist, a couple of years after moving to Éragny, he started working in the Neo-Impressionist style, but after a while gradually returned to Impressionism.

Surprisingly, perhaps, this painter of delicate,peaceful landscapes was politically a fervent anarchist, but his anarchism had nothing revolutionary about it; it consisted mostly of a great empathy for workers and a belief in equality for all.

In 1889, he made an album of ink drawings entitled “Turpitudes Sociales” illustrating the “misery and oppression” of urban workers, not for publication but just to educate his large family (he had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood).

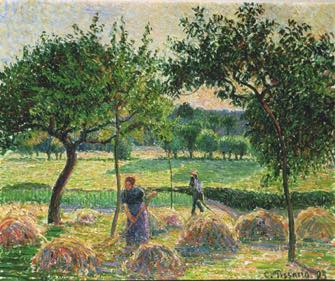

Workers in the countryside were another favorite subject, and many of the paintings here depict idyllic scenes of laborers at work in the fields or orchards around his home, which in spite of economic difficulties he managed to buy with the help of a loan from his friend Claude Monet.

These paintings make a nice change from the almost too-pretty landscapes. The latter are beautiful, certainly, but to my mind they don’t exhibit the genius of Monet, who always seemed to find an angle or intensity of color and light that made all the difference, taking his landscapes a step beyond.

My favorite part of the exhibition is the extensive series of drawings Pissarro made for a work called “Travaux des Champs” (“Field Work”). His son Lucien, also an artist (like all of Pissarro’s children and many of his descendants), whose paintings are hard to distinguish from those of his father, made prints of these drawings, and we get to see the different versions many of them went through as Pissarro père revised and refined them and reacted to the suggestions made by his son.

Lucien, by the way, owned the Éragny Press in London from 1894 to 1914, and the exhibition also includes a number of the handsome works by various authors he published with his own illustrations.

Favorite