|

|

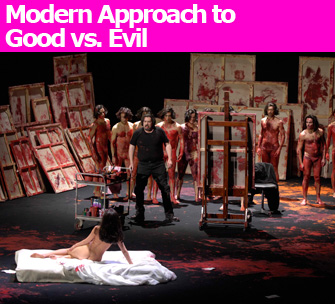

Blood-covered near-naked men add to the air of orgiastic intensity. Photo: Opéra National de Paris |

To say that the first Paris performances of Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser, about an artist torn between the lure of sensuality and that of spirituality, were not a success would be something of an understatement. Wagner himself came to oversee the production in 1861, and, predictably, given his legendary extravagance, proceeded nearly to bankrupt the Paris Opera with his various demands. It was said that the costs amounted to 300,000 francs (an enormous amount today, let alone 150 years ago), with a vast orchestra and a large array of extras, including horses and hunting dogs. Yet Wagner also had to contend with a notoriously conservative public who liked shows with tunes. When one critic wrote waspishly, “The 12 dogs were extremely handsome, but we would have preferred 12 melodies,” it is not difficult to feel some sympathy for the composer. But Wagner also made the cardinal error of not cultivating both the press and the various cliques within the audience, and the chaotic scenes led to the production being cancelled after only three performances.

Alongside those who drowned out the music with howls of derision (no mean feat, considering the large orchestral forces) at the first performances were some discerning spectators, not least the poet Charles Baudelaire, who was overwhelmed by Wagner’s vision of the struggle between good and evil. He wrote, “While Wagner comes close to antiquity in his choice of subjects and dramatic method, he is currently the truest representative of modern nature in the passionate energy of his expression.” Those words were prescient, as both the themes and musical expression of Tannhäuser acted as a springboard toward such extraordinary operas of Wagner’s later years as the Ring Cycle, Tristan and Isolde, and Parsifal.

Flash-forward to 2011. A few descendants of those earlier opera-goers were clearly present at the opening night of this new production at the Opéra de Paris Bastille: they booed Robert Carsen’s stylish and exciting staging. Fortunately, the cheers of more enlightened spectators were much louder than the jeers, and the acclaim for singers, conductor and orchestra alike was unanimous.

Although the modern updating made the many moments of excess shows of piety in the opera less believable, Carsen is never short of ideas that, by and large, work triumphantly. I loved the recurring leitmotif of paintings being carried across the stage (their subject matter not visible to the audience’s view). Symbols of orgiastic self-indulgence (if the sight of several near-naked men cavorting in red paint does it for you, make sure you don’t miss the first act) gave way to crosses held aloft by pilgrims in the final act. And, although rather too many productions these days use the stage to mirror the audience, Carsen’s decision to place the virginal Elisabeth (sung by the wonderful Swedish soprano Nina Stemme) in the auditorium itself as she performs her glorious second-act welcome aria was inspired.

Stemme is a great Wagnerian soprano in the making. If she continues to sing and act with such consistent quality, she may soon be rivaling her countrywoman Birgit Nilsson for the ultimate crown. As Venus, the diametrically opposed epitome of carnal lust, Sophie Koch is suitably alluring and strong-voiced. Like so many of Wagner’s lead tenor roles, the role of Tannhäuser is difficult both vocally and dramatically, but British tenor Christopher Ventris, while not scaling the heights achieved by the two female protagonists, manages to convey lust and high spirituality with equal conviction. My worry for him is that, given the dearth of talented heldentenors in the world, he will be overused in Wagnerian roles, and this may be detrimental to his voice. It is easy to see why Stéphane Dégout is gaining a fine reputation as a Lieder singer; in his performance as Wolfram von Eschenbach, he manages both subtlety and lyricism.

Mark Elder marshals the large orchestral forces with vigor and vision, and the Orchestra and Chorus of the Opéra National de Paris are in very fine fettle. For those of you who find later Wagner operas just too long, this one weighs in at a mere 4 hours and 20 minutes (including intermissions). Get a ticket if you can; it’s well worth seeing, even without horses and hunting dogs.

Opéra National de Paris: Place de la Bastille, 75012 Paris. Métro: Bastille. Tel.: 0 892 89 90 90 or + 33 (0)1 71 25 24 23 (from abroad). Remaining performances: October 9 and 23 at 2:30pm; October 12, 17, 20, 26 and 29 at 7pm. Tickets: €5-€180. www.operadeparis.fr

Support Paris Update by ordering music and books from Paris Update’s Amazon store at no extra cost. Click on your preferred Amazon location: U.K., France, U.S.

Reader Reaction: Click here to respond to this article (your response may be published on this page and is subject to editing).

© 2011 Paris Update

Favorite