For much of the 19th century, Britannia ruled not just the waves but most of the known world. Presiding over a vast colonial empire with an unrivaled productive capacity, Great Britain imposed its hegemony pretty much everywhere and on everybody.

Beyond its strength as a military and economic power, as the hub of a global trade and communications network, it exported manufactured goods along with the ideas, practices, tastes and lifestyles to go with them.

Of course, it had its rivals, chief among them France, with its own imperial, intellectual and cultural heritage. Frères ennemis, frequently oscillating between cordial dislike and entente cordiale at the political level, they were culturally and commercially more interlinked and mutually respectful than is often recognized.

An exhibition at La Piscine, a museum of decorative arts in Roubaix, a small town in the northeastern French industrial belt, is a brilliant (and timely in the post-Brexit era) reminder of the relationship between the two countries. “Roubaix Save the Queen,” running through January 8, mines the museum’s permanent collection to spotlight the relationship between the 19th-century textile manufacturers of Roubaix and the British textile industry, centered in Manchester. Tartans, tweeds, Paisleys and Liberty floral prints bear witness to the influence of British tastes on French textile designs.

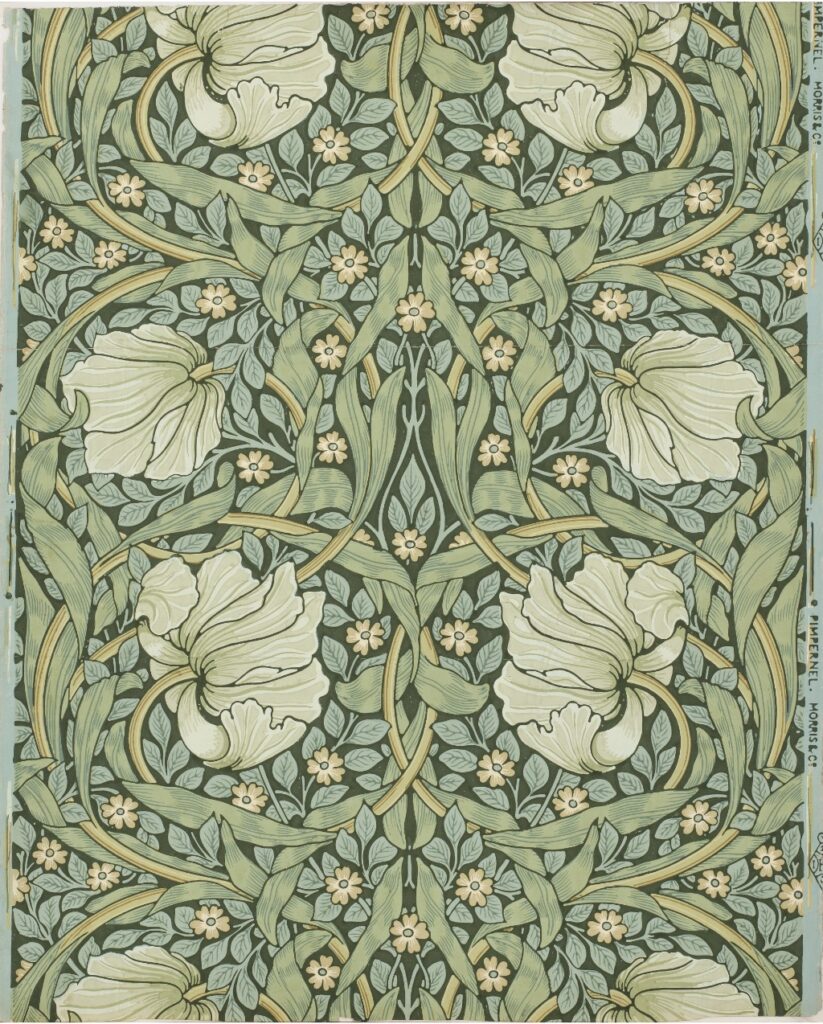

At the heart of the show, La Piscine is also paying tribute to the designer William Morris with the exhibition “William Morris: Art in Everything.” Morris was the iconic designer for Arthur Liberty, founder in 1875 of the London department store famed for its essentially French Art Nouveau style.

A polymath textile designer, writer, poet, painter, graphic artist, architect, craftsman, militant socialist and ecologist, Morris was the utopian theoretician of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Born into a comfortable middle-class milieu and educated in classical humanities at Oxford, Morris developed a philosophy that combined an idealistic moral socialism with fashionable romantic medievalism and a humanist belief in the importance of art and craftsmanship as a bulwark against the dehumanizing mechanical utilitarianism of the Industrial Revolution.

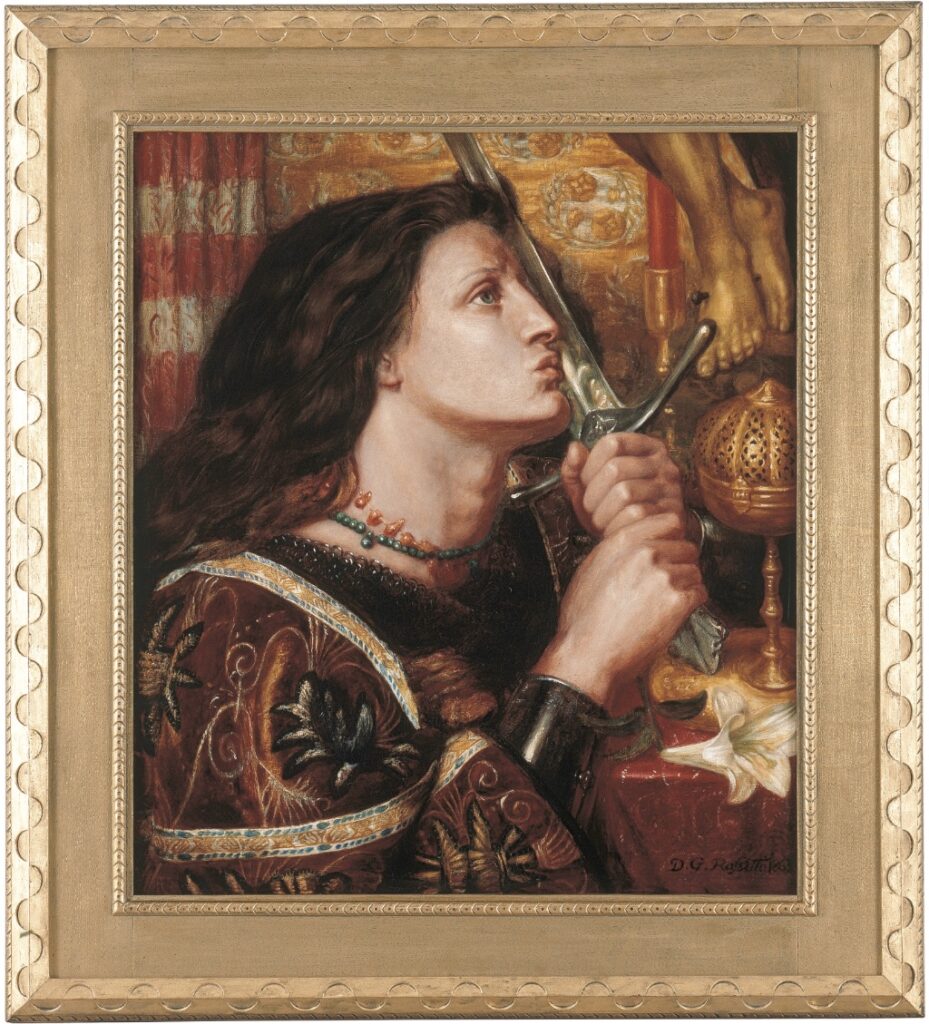

In Oxford, he bonded with Edward Burne-Jones, a would-be artist who was the son of a middle-England industrialist. Through Burne-Jones, he meshed with the group of aesthetic romanticists – Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others – known as the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Starry-eyed idealists perhaps, but when they went into business together, in a firm that came to be known as Morris & Co., the result was a set of exquisitely formalized designs, perfectly suited to reproduction in the Roubaix textile mills.

It was a style that chimed with the tastes of Victor Champier, creator in 1881 of the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Industries Textiles, the industrial arts and textile school that gave birth to La Piscine.

Through some 100 works of art lent by other museums, including Tate Britain, Victoria and Albert, the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, the show immerses visitors in Morris’s world. In wallpapers and wall hangings, furniture, paintings and drawings, it explores the symbiotic relationship between the manufacturing industry and craft designers. Despite the misgivings of the craftspeople and designers, it succeeded in creating an artistic vision of an ideal world within reach of a rising, aspirational mass middle class.

Before it was a museum, La Piscine was the communal swimming pool of a town that prospered and faded through the 19th and early 20th centuries with the rise and decline of its cloth-manufacturing industry. The museum was founded in 2001 to save this masterpiece of 1920s Art Deco architecture from decay. Expanded in 2018 into the remains of an abandoned mill, it has earned a reputation as one of the best French museums outside of Paris. A couple of hours by train from the capital (and a million miles away in terms of communal solidarity and gritty spirit), it’s worth a visit in its own right. With this show, even more so.

Favorite

I always read Paris Update as soon as it comes in. Such great things and often the subject of notes for our next trip to Paris. And the writing is such a pleasure to read. Consistently excellent.

Now enjoy your well-earned holiday. See you later in January.

Thank you!